You’re screaming out curses, you’re ready to throw your controller at the screen, your blood pressure has spiked to dangerous levels — and you’re having a fantastic time. There’s little else in life other than a well-crafted, incredibly difficult videogame that can be so thoroughly aggravating while simultaneously entertaining.

The only problem is — they’ve mostly ceased to exist.

Except for a few notable hold-outs (like, say, modern iterations of the Ninja Gaiden or Shinobi series) the days of the hard-as-nails game seems to have passed from mainstream publishing. Luckily, where there is a void in art, indie creators are almost surely working on filling it. Enter the recent resurgence of tough games from small developers and the rabid fan followings that have accompanied the release of titles like Super Meat Boy, Demon’s Souls and VVVVVV.

Something Easy This Way Comes

The renewed creation of extremely difficult games is, in many ways, a product of the time. As mentioned before, where something is lacking in an artistic landscape, someone will almost always notice and work on compensating for it.

But why is the videogame industry, once so full of sweaty-palmed platformers and punishing RPGs, now dominated by titles that can be beaten while requiring little more than a set of opposable thumbs and sufficient spare time (with the Wii, Kinect and Move you could even strike off the latter point)?

The answer lies in a simpler time: the era of the arcade.

Arcades, like any other commercial enterprise, are designed to make money. Every cabinet, from the lone, drink-ringed tabletop shmup in a ‘90s bar to any of the sophisticated, sit-in racers of a multi-level arcade serve one purpose: to wring as many coins out of customers as possible — and promptly deposit them into the hands of the establishment’s owner.

In order to properly accommodate this, arcade games in the 1980s and through to the few surviving units still installed today have been developed in order to create a carrot-and-stick level of risk and reward for players. While the games themselves had to be fun, the bottom line of this approach centres on how best to make a given title hard to advance in, ultimately something that works to increase profits. Because the “arcade experience” was the contemporary watermark of technology, early consoles sought to emulate it and, accordingly, the first Nintendo, Sega and Atari home entertainment systems were inundated with incredibly tough games. Over time, as technology continued to evolve and the game industry became more enticing for a larger segment of the population, most mainstream games began to lose their punishing edge.

Our current, massively growing videogame industry is, not unlike arcades, designed to make as much money as possible. And just as the arcades were able to find the right recipe for success by installing scores of quarter-consuming cabinets, the contemporary game industry has sought to maximize profits by appealing to the widest possible audience.

Easier games are more appealing to more potential players because, simply enough, anyone can find enjoyment in them. Some of us may cherish the memory of finally seeing the credits after beating the last boss of a gruelling Mega Man or Castlevania title because there was a level of devotion that was required to reach it. But that same type of satisfaction — the kind that results from overcoming difficult odds — is exactly the sort that bars the “casual” or novice gamer from entry. Thus, game developers and publishers began to move away from the kind of titles that required intense concentration and refined skills. They instead focused on making it simpler to reach the game’s end (and provide closure on an interactive experience) in order to get as many people on board as possible.

Whereas difficult arcade games were designed to keep players pumping quarter after quarter into them to yield profits, it now makes better financial sense to have players pumping money into more and more individual games that reach their conclusions more quickly.

The Indies Respond

This recent rebirth of truly challenging games can then be seen as a natural response to the trends of the majority. Because current multi-million dollar, focus-tested videogames can be breezed through by nearly anyone, the smaller, less financially risky passion projects of small teams have sought to fill the hard-game vacuum left behind.

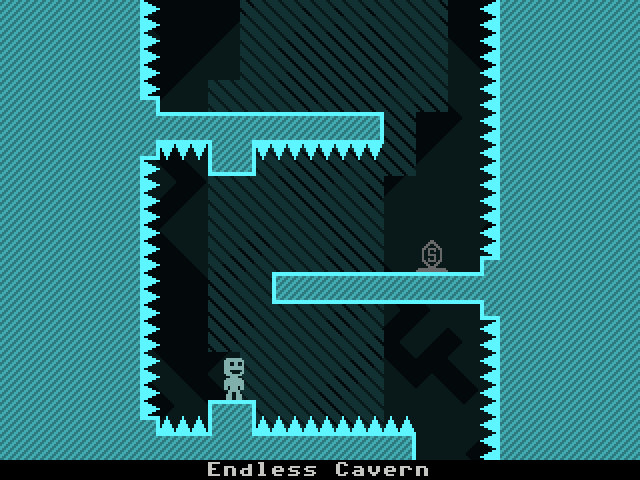

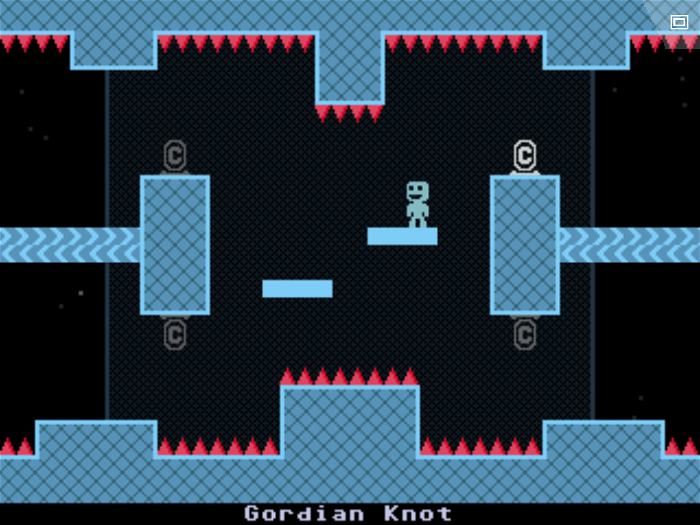

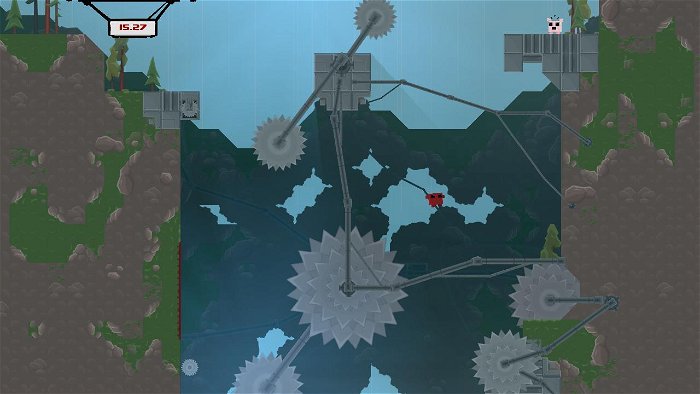

In recent years indie developers have tapped into the masochistic urges of many gamers by providing them with titles like Terry Cavanagh’s Flash-based VVVVVV, PC and XBLA megahit Super Meat Boy or Playstation 3 exclusive Demon’s Souls. Each of these games was created by small teams: Demon’s Souls was developed by Japan’s fairly obscure From Software and imported to the West by Atlus, a company known for publishing niche RPGs and strategy games, Super Meat Boy is the result of the two-man Team Meat studio (consisting of Edmund McMillen and Tommy Refenes) and VVVVVV was crafted entirely by Cavanagh.

When looking at sales charts and Metacritic score aggregates it’s easy to see that this hasn’t been a wasted effort. The three titles listed above, as prime examples of critical and commercial successes developed by small studios, demonstrate that there still exists an audience of gamers, hungry for a more challenging experience.

Super Meat Boy and VVVVVV both came out of the gate strong with their launches, VVVVVV garnering praise for its inventive mechanics, stunning chiptune soundtrack and tight design ethos and Meat Boy sweeping the XBLA charts (before making a much-anticipated arrival on PC) on the strength of its quirky characters, offbeat sense of humour and retro-inspired platforming. Demon’s Souls demonstrates the kind of success that an indie word of mouth sensation can enjoy. Although its 2009 release (2010 for those always-neglected European gamers) was quiet enough, the following years since launch have seen it gaining in sales until, now, it sits just a few purchases away from reaching the milestone of one million units sold.

And the development of these kind of experiences show no sign of stopping.

From Software is already hard at work on Demon’s Souls’ spiritual successor, Dark Souls and, understanding the reason why so many players raved about their previous title, the director of both games, Hidetaka Miyazaki, has promised an even more punishing experience with its “sequel.” Super Meat Boy has continuously grown in popularity from its browser-based beginnings (as Meat Boy on Newsground) to an XBLA sleeper hit and successful multiplatform present. VVVVVV holds a devout cult following of players and has provided its creator, Terry Cavanagh, with the kind of success and name-recognition necessary for working on further indie titles (like the recently released American Dream).

And now that the indies have shown the way, as always, the mainstream can start to absorb their lessons and incorporate them into business as usual. We can now expect to see a better balance of hard and easy games emerging in the future as the indie studios’ financial evidence (the arbiter of all industry trends) points to the fact that these two styles of play can coexist.

There’s enough room in the videogame marketplace for there to be games of all kinds. Easy, “casual” games like Kirby’s Epic Yarn can still sit on the shelves (and gain as much critical praise) as difficult, “hardcore” games like Demon’s Souls.

This is a good thing.

As the videogame industry continues to expand and advance itself as a viable entertainment (and artistic) medium, it needs all the expressional tools it can lay its hands on. Knowing that money can still be made, whether a title is excruciatingly tough or welcomingly easy, is important for ensuring that we all get the best possible product in the end.

This is originally appeared in the 2011 March issue of CGM.