There was a time in gaming when the player had the option to not just don some high-tech space armor and shoot things. They could also strap into a starship and take to space, dog-fighting against alien fighter craft, or slide into the control pod of a giant, bi-pedal robot on a dusty alien world and pepper similarly towering opponents with missiles and rail gun rounds. But all of that has been largely taken away from us, except as an occasional break from first person shooting. Why? Before we attempt to answer that question, perhaps it’s best to start at the beginning, and see what it is we’re missing now.

Star Wars Dreams Come True

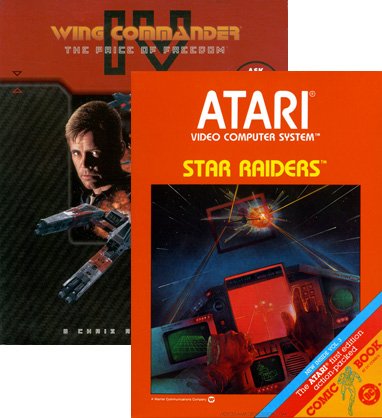

In 1977, when the original Star Wars came out, millions of boys across the planet had their imaginations fired up by the most realistic depiction of space fighter combat in space seen at that time. The infamous attack of the Death Star showed everyone what futuristic vehicular combat could be like, and new dreams were born. In the same year, a company known as Cinematronic released a vector game in arcades known as Starhawk, that put players in the seat of a fighter flying down a trench while enemies (at least one of which looked suspiciously like a TIE Fighter) flew by. The game was little more than a shooting gallery, as players could only control their targeting reticle, but it gave people a chance to virtually experience the final famous scenes of that year’s biggest movie. Just two years later, in 1979, the grand daddy of all hardware developers, Atari, would take an important next step. In an attempt to promote their fledgling line of personal computers, the 400 and 800 series, Atari released Star Raiders. The game’s premise was simple; players sat in the virtual cockpit of a high-powered space fighter and warped to different sectors of space to engage in combat with enemy fighters. The game was firmly locked in a first person, cockpit view, gave full control of maneuverability to the player, and included unheard of features at the time like a galactic map for navigation to different areas, tactical radar, one life that was used up once ship shields were gone and the fighter took a direct hit, and cumulative damage, with players experiencing performance failure of various ship systems as damage piled up. Players could even warp to friendly areas in order to repair damage at space stations before returning to the fray. This enormous amount of complexity finally gave players a small taste of what it would it would be like to pilot a fighter in space, and it was from this that a genre was born.

In 1977, when the original Star Wars came out, millions of boys across the planet had their imaginations fired up by the most realistic depiction of space fighter combat in space seen at that time. The infamous attack of the Death Star showed everyone what futuristic vehicular combat could be like, and new dreams were born. In the same year, a company known as Cinematronic released a vector game in arcades known as Starhawk, that put players in the seat of a fighter flying down a trench while enemies (at least one of which looked suspiciously like a TIE Fighter) flew by. The game was little more than a shooting gallery, as players could only control their targeting reticle, but it gave people a chance to virtually experience the final famous scenes of that year’s biggest movie. Just two years later, in 1979, the grand daddy of all hardware developers, Atari, would take an important next step. In an attempt to promote their fledgling line of personal computers, the 400 and 800 series, Atari released Star Raiders. The game’s premise was simple; players sat in the virtual cockpit of a high-powered space fighter and warped to different sectors of space to engage in combat with enemy fighters. The game was firmly locked in a first person, cockpit view, gave full control of maneuverability to the player, and included unheard of features at the time like a galactic map for navigation to different areas, tactical radar, one life that was used up once ship shields were gone and the fighter took a direct hit, and cumulative damage, with players experiencing performance failure of various ship systems as damage piled up. Players could even warp to friendly areas in order to repair damage at space stations before returning to the fray. This enormous amount of complexity finally gave players a small taste of what it would it would be like to pilot a fighter in space, and it was from this that a genre was born.

From here even the lowly Atari 2600 would reach out to space fighter fans with titles such as Starpath’s Phaser Patrol, Activision’s Starmaster and Imagic’s Star Voyager. Console rival Mattel responded in kind with Star Strike and Space Battle among others on the Intellivision. While these console variants of Star Raiders worked well enough, they were severely hampered by one thing. They lacked the plethora of buttons available to computer users that had a keyboard. Because of this, combined with the computer arms race of increasing graphical prowess and constant flow of new peripherals such as flight sticks and driving wheels, it was on the IBM PC, which eventually crushed other competitors such as the Atari and Commodore computers, that space fighter simulators would thrive. And it would give rise to a new kind of science fiction simulator that would go happily toe to toe with its starship relative; the giant robot.

The Renaissance Begins

In 1989, Activision working with the Battletech license from table-top role-playing game company FASA, released MechWarrior. The game was set in a far flung, galactic feudal society in which combat was conducted with advanced, massive bi-pedal robots clearly inspired by the mecha anime of Japan from earlier years. Players had to deal with new technical limitations such as weapons fire being limited by heat sinks, as well as persistent damage that would carry over into new missions unless repairs were conducted. An uncanny level of tactical realism was being introduced into these futuristic simulators, and just one year later, the doors got blow down completely.

From 1990 onwards, futuristic, fictional simulation enjoyed a golden age it would never know again. 1990’s Wing Commander by Origin Systems raised the bar for the entire genre by introducing a higher level of graphic fidelity, voice work in subsequent expansions and a cinematic storyline that would eventually give rise to a terrible film adaptation in 1999. It also refined many evolving mechanics of the earlier titles in the genre, giving players the ability to pilot different ships, issue battle orders to AI wingmen, and take fuel, fire and shield consumption rates into consideration during battle. The combat itself finally gave players the freedom to bank, pitch and yaw at high speeds in space giving PC users an excuse to use those flightsticks for something other than flight simulators. Wing Commander went on to become an incredibly successful series who’s prominence in the space fighter simulation field would only be rivaled by one other franchise; the source of all the inspiration.

Star Wars: X-Wing came out in 1993, and provided as compelling an experience as Wing Commander with one notable difference. It finally put players in the cockpit of the ship they’d been dreaming to pilot since 1977. X-Wing however, didn’t just coast by on the appeal of its intellectual property. Ship navigation and combat was both in depth and complex allowing for a wide variety of maneuvers and tactical possibilities, even giving players control of energy distribution to ship systems such as weapons, engines and shields. The missions were large, multi-staged and varied, often with objectives that rapidly changed as new developments occurred. Perhaps most importantly, X-Wing was also one of the pioneers in PC games to make the move to 3D polygonal graphics, as opposed to the sprites, a limitation previous franchises had to deal with until the emergence of more robust graphics cards occurred. Like Wing Commander, X-Wing would go on to spawn a series throughout the 90s, including TIE-Fighter, X-wing vs. TIE-Fighter—which finally introduced online play with free for all and co-op modes—and X-Wing Alliance.

On the console front, new, polygon pushing consoles such as the Playstation also jumped on board. Giant robot fans were served with titles such as Crazy Ivan and space combat enthusiasts had Colony Wars as, well as futuristic atmospheric combat with G-Police. But it was back on the PC that one of great landmarks in space fighter combat had finally been reached. Chris Roberts, creator of the Wing Commander series started up Digital Anvil, a response to the closure of Origin Systems by Electronic Arts. In 2000, Digital Anvil released Starlancer, which kept all the complexity and immersion of the Wing Commander series and added the additional feature of a full campaign that was fully playable in co-operative mode. At long last, players weren’t limited to focused skirmish activities in a multi-player specific mode, and could undergo the entire campaign with friends in a fully formed squadron. Starlancer also notable for making the jump to consoles—with multi-player intact—on the DreamCast. This was the pinnacle of the genre, but rather than go on to bigger and better things. Everything came to an abrupt halt.

Exiled To The Far Reaches Of Space

The 21

century was not kind to simulations of futuristic war vehicles. Starlancer, despite being the best the genre had ever offered, suffered low sales, and it seemed like Giant Robot Fever had also passed. Mechwarrior 4 had its final expansion, Mechwarrior 4: Mercenaries in 2002, and since then, almost no big budget titles have been released that put players squarely in the cockpit of a science fiction combat vehicle. Microsoft, owners of the Mechwarrior license for many years, attempted to keep the property alive by turning it into a 3

person, arcade-like action experience with games like MechAssault, but it was clear by this point that the time of such games had passed.

The question then becomes, “Why?” Why did one of the more substantial reasons to own a gaming PC or even a console with multiple buttons on the controller lose its appeal with the gaming audience? The answer is simple and it lies almost entirely on the changing tastes and growth of the audience themselves. As with many genres on the PC, the space/robot combat simulation was ill equipped to deal with the changes that were gradually creeping into the industry. Budgets and expectations for game technology rose, demanding a larger audience, but the ease of piracy on PCs tended to limit the growth of audiences. The rise of the MMO over the 90s had eroded the market for other genres on the PC as the persistent online aspect appealed to the players, while the monthly subscription was a boon to publishers as a way to finally combat piracy. And with the advent of online capable consoles such as the DreamCast and Xbox, the pull of multi-player games—and the console’s new found ability to handle a first person shooter with decent controls—made gaming a much more mainstream and financially lucrative affair on consoles.

Like an animal that fails to compete in an evolving ecosystem thanks to overspecialization, the increasing complexity and immersive qualities of the genre began to work against it. The fundamental problem became one of cost versus sales. As PCs and consoles grew more powerful, players expected an attendant rise in visual fidelity and content. This inevitably led to a rise in production costs for all genres of games, but certain genres, such as adventure games and science fiction vehicular combat simulators, were a niche with limited appeal to begin with. The smaller audiences translated into smaller sales that couldn’t justify rising budgets, and so a vicious circle was established. That wasn’t helped by the fact that publishers were now wandering into the territory of “mega-hits” with games with like Halo: Combat Evolved selling millions of units. It was a time when publishers and developers realized that simpler games translated into bigger sales. Accessibility and pick-up-and-play game design were what made games appeal to the masses. The starship or giant robot simulator was the anti-thesis of this, asking players to engage in tactical and strategic thinking, to consider aerial dogfight maneuvers while balancing damage and energy limitations. In other words, such games asked the players to work a little, when the best selling games were proving that easier held more mass appeal.

This is nowhere more apparent than the final swan song of such games on consoles. 2002’s Steel Battalion by Capcom is the most ambitious attempt from a publisher to try—and fail—to save this genre. Created as an Xbox exclusive, Steel Battalion did what no other science fiction vehicular simulation game had ever dared; Capcom manufactured a control panel specifically for the game. The game, weighing in at $200, included a full control panel with 40 functional buttons, levers, dials, two joysticks and foot pedals. No game since has ever taken into physical account every functional nuance of controlling an imaginary giant combat robot, and sadly, despite the greatest level of immersion ever seen in a game of this kind, Steel Battalion didn’t sell well. The high price tag, complex controls and more methodical gameplay put off most gamers, especially in the wake of the previous year’s much faster paced and simpler Halo, with its easy to use console multi-player features, something that Steel Battalion lacked. The game was critically admired for the boldness of its vision, but ultimately managed to just barely break even when its global sales were tallied up.

Since that time, MMOs, RPGs and of course, FPS games have been mainstays on the PC, while the consoles enjoy 3

person action games, FPS and RPGs as well. No publisher has released a major, fully-fleshed space combat or giant robot simulator in the years since, although simpler, more arcade-like titles such as the Armored Core series still try to carry on similar concepts. The starship as a fighter has also recently made a cameo appearance in Halo: Reach, when players briefly hopped into a fighter craft to take on the Covenant, though no cock-pit view was available, and many functions were stream-lined and simplified.

While it looks like the glory days the genre are well behind it, that doesn’t mean such games are entirely extinct.

Faint Rumblings From Beyond

There’s still not much information available, but it was announced in October of 2010 that Atari would be bringing Star Raiders back to the PC, Playstation 3 and Xbox 360. Early trailers show 3

There’s still not much information available, but it was announced in October of 2010 that Atari would be bringing Star Raiders back to the PC, Playstation 3 and Xbox 360. Early trailers show 3

person combat from the rear of the ship, while preview information hints at transformable fighters and multi-player. The game is slated for an early 2011 release, but it remains to be seen how true to the strategic roots of the series the newest iteration will remain. The other surprising reveal comes in the form of Steel Battalion: Heavy Armor. Published by Capcom and developed by From Software, creators of the Armored Core series, this new sequel is taking a radical new direction with the announcement that—as an Xbox 360 exclusive—it will feature Kinect functionality. It’s quite a surprise that a title with a dedicated controller would go the controllerless route, and both the industry at large and players are curious to see how this dramatic conceptual change will be executed.

The genre of starship combat and giant robots has been asleep for a good number of years. Perhaps the time away has made such gameplay attractive to audiences again. After all, for the last few years, they’ve been jumping into the boots of contemporary soldiers and space marines. Maybe they’re ready for change. Blasting fighters in space would certainly be a big one.