A few years ago I had the great pleasure to be sitting across from Neil Gaiman.

If you don’t know who he is, maybe the comic book series The Sandman rings a bell. Or the fact that he was the first comic book writer to win the World Fantasy Award. Perhaps Coraline or American Gods, both best-selling novels, strike a chord of familiarity. But none of that is quite as important as this; Neil Gaiman is one of the reasons I went into writing, and here I was, sitting across from him and being paid by an editor to ask him questions. Naturally, being a game journalist, one of the questions I asked as, “Do you like videogames? Which ones are your favourites?”

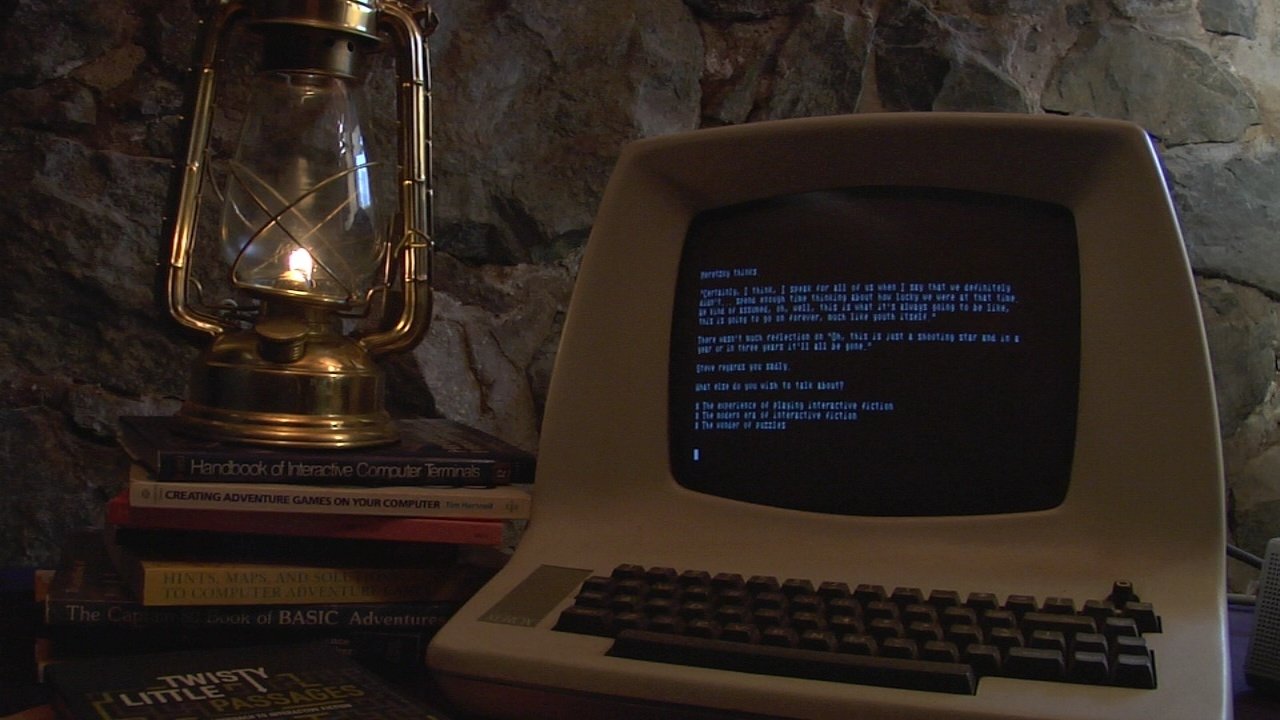

Neil Gaiman being Neil Gaiman gave a typically sideways answer. He said, “My favourite games are the old text adventures, because they had the best graphics.”

And through the years that answer has stuck with me, because there’s a lot of wisdom in that clever response. A deeper truth that so many of us in this high-def era forget.

“My favourite games are the old text adventures, because they had the best graphics.”No matter how much the platform of delivery may change, there is something about plain, simple text that has a timeless power. Words reach directly into your brain, tickling it, encouraging it fire away, to make connections, to think things and dream things that might otherwise have never entered. Fiction, the best of it anyway, has always had that power to engage the imagination. More than any other genre, the humble—and now almost endangered—text adventure is one of the most successful attempts at reaching the holy grail of games, truly interactive fiction. Just like the novel, the text adventure doesn’t have to worry about production values, a massive staff, or spiraling budgets because of special effects and demanding actors. The only thing the text adventure cares about is crafting a story in words. The defining difference from fiction is that you, the player, propelled the story forward and “talked back” to it.

If you ever remember being told a bedtime story as a child, you’ll remember what a different experience it was from being able to read a book properly by yourself. Your parents would tell the story, you would insist on doing things differently, telling things differently, trying other stuff out. If your parents were particularly inventive and gracious, they would flex and twist the story to your desires for the night. And that’s what text adventures do.

You still have the pleasure of experiencing a singular narrative voice, a particular style of telling things, hallmark signatures of portraying dialogue and descriptions. But you can decide what to do, where to go, what to take, who talk to and who to ignore. This is still fiction, there’s no mistaking that. It has a beginning, middle and end that crafted by one author. But everything that happens between those fixed points of the story can stretch and contract based on your actions. Companies like Infocom, and writers like Steve Meretzky, Mark Blank and even Douglas Adams accomplished with only words what David Cage or the doctors of BioWare strive towards with a small army of development staff; stories the player can interact with.

There are several moments in the Infocom version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy where you, as a player get a sense of Douglas Adams that you just can’t get with the original novel. You say things, do things, pick things up, and at every step of the way, Douglas Adams is there, surprising you with his responses. Unlike the original novel where you are being told an adventure by Douglas Adams, the Infocom game feels like you and Douglas Adams are going on an adventure together.

Right now the number of people that still convey that sense of a singular vision in a tale you help shape can be counted on one hand. But when you take the time to look in the nooks and crannies of the internet for the corners where Interactive Fiction still lives—and is mostly free—that sense of individual artistry explodes. Perhaps it’s time for more of us to go beyond the graphics we see on the screen and enjoy the graphics that Neil Gaiman found so engaging; the ones in your head.