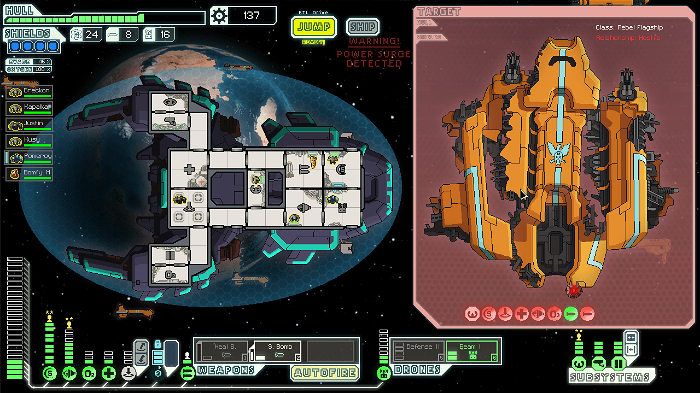

Subset Games’ FTL: Faster Than Light is a tough game to describe. It both does and doesn’t belong to the “roguelike,” role-playing game, simulation, or strategy genres. Rather, it’s a blend of the best parts of many different types of games that ends up feeling like an altogether new kind. This is a good thing since any attempt to shoehorn FTL into a single genre would probably have resulted in a game that isn’t nearly as unique or interesting to play.

Despite liking it a great deal now, I didn’t quite get FTL when I first picked it up. For whatever reason—and by no real fault of its design—managing my spaceship and its crew’s flight across the galaxy just didn’t click. Part of this is probably due to my playing it in short bursts during the busy holiday season and not having time to properly explore the game’s many different systems. Another reason is that I think I expected something a lot more formulaic than what I experienced. FTL‘s Steam page lists its genre as “Indie/Simulation/Strategy.” This is a fair enough description, but it is also a bit misleading. The “indie” descriptor, in games as in music, is incredibly ambiguous and offers no information whatsoever as to how the game plays. Trying to pin FTL down as a strategy or simulation game is a bit more helpful, but not by much. When I picked up the game I was expecting something different, because the genres it was assigned don’t do a good job of describing what it actually is.

I’m not blaming Steam (aside from the silly “indie” label) for failing to find a better way to categorize FTL, though. Not being able to assign a neat label to every game is a problem without a very clear solution—there have been a number of times that I’ve been stumped by trying to accurately fill out the details of a game’s genre at the header of a review, after all. It’s difficult to see what titles like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim and Final Fantasy XIII, both role-playing games, have in common aside from the ability to upgrade characters with skill points and new equipment. Just the same, games magazines, website, and digital storefronts are trapped by genre labels since they’re one of the most concise ways to inform audiences of what kind of experience to expect from a given title. In a lot of cases it’s possible to categorize art and entertainment in a manner that makes sense (calling Battlefield a first-person shooter is accurate), but it’s just as likely that a game like FTL comes along that defies easy categorization.

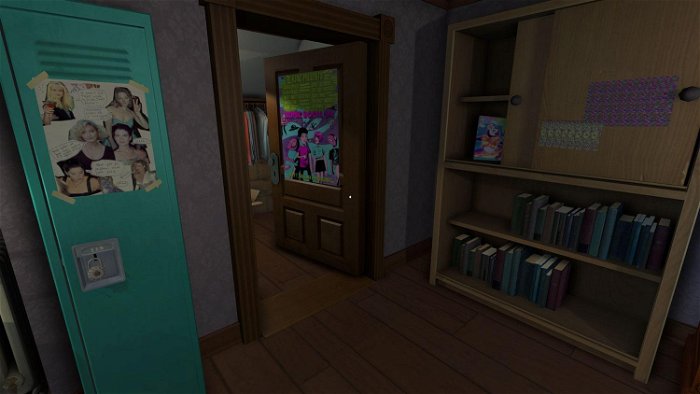

None of this would be very important if it wasn’t for the fact that genre classifications can be incredibly important in game development and marketing. Potential buyers who don’t care to read full-length reviews or watch player-made videos can still get an idea of what a game is through a genre description. Someone who liked Assassin’s Creed will probably enjoy Uncharted, since both are loosely related as “action adventure” titles; a fan of Portal may enjoy Antichamber, another puzzle game, even if the two experiences are fairly different in tone and mechanics. Where these descriptors become less helpful is in situations where a developer’s willingness to experiment with game styles may be stifled by a mandate to stay within arbitrary genre boundaries. One of the best known examples saw Double Fine Productions’ fantastic Brütal Legend facing critical backlash for introducing real-time strategy mechanics to a title that was initially billed as a straightforward action game. The Fullbright Company’s Gone Home, a game that seemed like it belonged to the horror genre until players discovered it was a more realistic coming of age story, found its detractors as well. The lesson for onlooking developers and publishers working in the mainstream of the industry may have been to avoid this kind of experimentation in future.

What’s interesting about this, though, is that both Gone Home and Brütal Legend are games that found a lot of success outside of the mainstream videogame market. The reason for this is probably similar to my own reaction to FTL. At first it was a game that was confusing because it failed to conform to the genre descriptions placed on it; later it was exciting for that same reason. Titles that experiment with style and end up blurring genres may be harder to describe and sell, but they’re often the most innovative and worthwhile ones, too.