I can still vividly remember the night I spent trying to sleep with the lights on after going to see The Blair Witch Project at the movie theatre. I’d been scared by horror movies before, but never really shaken up to the extent that I was for those long hours. As I lay in bed, trying to think happy thoughts, my mind invariably returned to the shadowy images that the film had painted its monster in. These were crafted not by visuals, but through a collection of early-movie interviews with “locals,” historical background, strange discoveries in the woods and, of course, the heart-stopping finale with all those unbearably creepy child handprints littered across the walls of the abandoned house in the movie’s last minutes. Nothing else has ever frightened me quite as much as that film.

Over the years, I’ve seen many more horror films (usually devouring a year’s worth during October and then mostly ignoring the genre for another eleven months) that have tried to recapture the eerie atmosphere and blood-curdling scares of The Blair Witch Project, but most of them have missed the mark.

Videogames, for the most part, have fared much better in getting to the spirit (pun intended) of the found footage classic. While there are myriad horror games that more closely resemble less successful fright flicks (how many games function as glorified slasher movies after all?), others understand how to channel the fear of unknown threats into truly terrifying experiences.

The titles listed do this in different ways, all unpacking the essence of a terrifying “other” in different ways.

Dead Space and Understanding the Worst Kind of Monster

Dead Space is frequently creepy, but rarely outright frightening — except for in the opening hour of the first game in the series. During this stretch of time its developer, EA Redwood Shores (now renamed to Visceral Games), offers players a brilliantly tense exercise in space terror, the uneasy suspense of its mystery and menace owing much to films like Event Horizon and Alien. When protagonist Isaac Clark and his crew of seemingly hapless engineers dock at the eerily abandoned Ishimura, looking to discover the source of the distress signal being broadcast from the giant spaceship, they are greeted with nothing more than a deathly silence.

The omnipresent hum of sterile air systems and halogen lights all suggest that everything is in normal order, but glimpses of vast, chaotic space from occasional portholes (and, later, the requisite blood smears) keep players on edge. Dead Space introduces itself with such breathless tension that it’s almost a disappointment when the crescendo of its spooky sounds and hints of diabolical activity climax into the appearance of a well-designed, but eminently killable, monster.

The introduction of these Necromorphs, Dead Space’s resident bad things, breaks the spell that the game had established up until this point. When one of the creatures first appears it is, of course, appropriately creepy, but all of its gross spindly limbs and distorted, vaguely human face are no match for Isaac’s gun. Once defeated, the monsters are no longer as horrible as they were when confined to shadows.

This is because they have taken on a real shape — something that the player can wrap their mind around. Dead Space has to show its monsters if it wants to function as an action game and this is where it loses most of its power. When the creatures are understood and have taken shape as a concrete threat that can be eliminated with sufficient firepower, they are no longer as menacing as when the player is able to fill in the blanks with their mind.

At this point Dead Space stops being terrifying and starts being a (still really fun) horror-tinged shoot-out. It may seem like this loss of fear is a necessary feature of any spooky action-oriented game, but examples exist that argue otherwise.

Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines and Powerlessness

Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines casts the player as a tough-as-nails, super-powered bloodsucker prowling the streets of Los Angeles as s/he learns to navigate the city’s underground vampire scene. For much of the game there are enemies that must be dealt with — rival vampires, ghouls and the occasional werewolf — through the game’s combat mechanics, but nothing that provides a real threat beyond having to reload a prior save.

Ocean House Hotel, a haunted old mansion that the player is sent to investigate a few hours into the game, changes this. The old building validates the rumours of ghostly activity early on, shadowy figures lurking in far-off doorways and mysteriously shaking chandeliers or vases reinforcing the local legends the player has heard from other characters before entering. Ocean House turns out to be far worse than Bloodline’s audience could have predicted.

The player’s customized vampire protagonist begins investigating the creepy hotel, perhaps thinking (despite the game’s overt supernatural tone) that the paranormal phenomenon could be the work of some rival gang of vampires. Spooky objects moving on their own is a bit unnerving at first, but nothing too bad. The game then kicks the section into high gear by guiding the player through a hallway where the rotted floorboards give way. Landing in the basement of the grand old hotel, the previously strong vampire is now fully out of her or his depth, less poking through the mansion now than struggling to survive against its menacing apparitions.

The entire Ocean House Hotel sequence is a brilliant meditation on how to scare players out of their wits by refusing to show them exactly what it is that lies behind the horror. By picking up old newspapers and observing the environment, clues as to the nature of the ghosts haunting the player can be ascertained without ever being completely explained. Aside from unexpected sounds and suddenly moving objects, the game never shows its entire hand. The terror of the hotel is sustained — and lingers long after — because most of it is created in the audience’s mind, only having been prompted by Bloodlines’ developers.

The rest of the game offers the player a typical videogame power fantasy — other enemies, no matter how terrible, can be defeated — but the Ocean House Hotel demonstrates how effective horror can be when it strips away the abilities we take for granted when normally confronting threats in games.

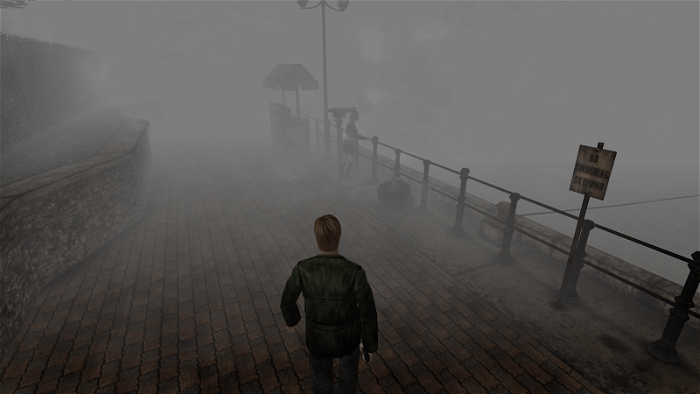

Silent Hill and Technical Limitations

The fog that blankets the town of Silent Hill sets the tone of the series’ first entry perfectly. It makes the town feel isolated, its secrets hidden from plain view and almost always promises to be hiding something menacing just out of sight. Although the weather and lighting effects were borne of the technical limitations of the PlayStation, the oppressive fog and shadows of the game ended up lending Silent Hill a trademark look — and one that would go a long way toward establishing Silent Hill’s legendary creepiness in the years following its release.

The muddy graphics and indistinct environments may not have been what Konami’s Team Silent would have wanted to portray if they had access to more powerful technology, but the boundaries of the original PlayStation end up making the first Silent Hill perhaps the most memorable of the series. This is because every horrible monster that the player’s mind can conjure up actually exists in this game.

When main character Harry Mason arrives in Silent Hill he is forced to contend with a seemingly endless sea of grey, the air impenetrably clouded everywhere more than a metre or two from his line of sight. Once he enters a building, shadows obscure the environment in a similar manner. These design elements make every unexplainable sound (and the sound is excellent in Silent Hill) almost unbearable. The quiet of an abandoned street is broken by echoes of something in the distance and the player knows that they are not really alone; a creaking floorboard, whispered voice or sudden thud while exploring a spooky elementary school serve the same purpose inside.

Because the monsters are rarely seen (and because, once they do appear, their twisted forms are crudely rendered enough to make them only a slightly filled-in canvas) they get to become whatever the player fears most. Like Bloodlines ghosts and Dead Space’s pre-reveal Necromorphs, the fear is in the imagining, not the seeing.

The addition of a radio early on only serves to heighten the suspense. Harry discovers that the faint hiss of static coming from the device’s speakers grows louder and louder as an enemy approaches. This has obvious tactical advantages (preparing a weapon is timely and cumbersome) and also enhances the sense of dread that the outdoor fog and indoor shadows create. Team Silent grabs a hold of our lizard brains, reverting us back to nighttime mammals who enter adrenaline overload when we hear a snapping twig or spot a strange shape just outside of the light of the campfire.

Amnesia, Slender and Oppressive Atmosphere

The creatures that lurk just outside of our vision are, as shown by Silent Hill, Bloodlines and Dead Space, the most frightening. In the last year, no two games have capitalized on this crucial element of horror more effectively than Amnesia: The Dark Descent and Slender: The Eight Pages.

In Amnesia the setup is fairly standard: Daniel wakes up in a castle without any memory of how he got there and must, like the player, discover why he is where he is and what exactly is going on. Before long his search has taken him into a badly-lit cellar where the air seems to grow almost physically heavy with a sense of foreboding. Barely audible noises and shapes from the corner of the eye introduce players to Amnesia’s most effective mechanic: a “sanity metre.” When the sanity metre depletes the frame of view becomes shaky and distorted, staying like this until some sort of reprieve can be found.

This design choice encourages players, ingeniously, to both fear the darkness and avoid getting a good look at the creatures pursuing Daniel from room to room. Because there are no weapons available in the game, Amnesia’s audience must play along with its downright mean-spirited mechanics if they wish to keep playing/not turn Daniel into a quivering lunatic. More than just a test of bravery, Amnesia is also one of the strictest adherents to the Blair Witch principle of hiding the monster at all costs. It is possible to see the source of Daniel’s terror in the game, but doing so causes his sanity to tailspin and will likely require reloading a save point to recover from.

Slender is less complicated than Amnesia, but very much follows in its footsteps. In it players are tasked with the simple goal of locating eight scraps of paper from within a stretch of forest. They are armed only with a flashlight on their mission and are being actively pursued by a spooky thing called Slenderman. The noises from feet crunching across the gravel paths and fallen leaves of the forest are the only sounds at first. Then, while exploring, deep industrial booms begin to echo in the background, intensifying when moving in different directions. Very quickly, the player learns that the volume of this sound and the presence of an encroaching layer of static over the screen signify the approach of Slenderman.

Once the audience’s heart begins pounding it becomes difficult to continue concentrating on finding the pages and the game transitions to a test of willpower. Is it smarter to get away from the monster hunting you down or stay the course and try to find the rest of the pieces of paper? Slender is effective horror because its mechanics tell players to do everything in their power not to look at their predator. Active avoidance and the sound and visual descent into panic make for a game that is truly terrifying. By the time the player actually sees Slenderman it almost doesn’t matter that the creature is rendered in such a comically sloppy way. No monster, no matter how expertly designed, can live up to the fear that pre-empts its appearance.

Horror can be an incredibly effective genre when handled thoughtfully. Videogame horror in particular — interactivity being the medium’s core element — is able to make audiences frightened in a unique way, offering something that can’t be attained through the more passive scares of books or films. Those developers who have thought hard on what does and doesn’t work in the genre are able to create games that take the idea of “fear as entertainment” to a new level. Well executed horror games invite thrill seekers to test the limits of their willingness to experience terror by actually requiring them to take part in their own scares. No one forces anyone to keep playing, after all.

The same element always returns in each of the best horror videogames, though: our innate fear of the unknown. Thoughtful creators know that leveraging this distinctly human Achilles heel can lead to entertainment that makes an indelible impression on its players. Every time videogame developers bring innovations to the medium they are also giving horror fans new ways to face this fear, giving the bravest players different opportunities to wrestle with the depths of their own nightmares.

This article first appeared in the Oct 2012 issue of CGMagazine.