Recently I was talking to a producer working at one of the big, AAA publishers and naturally the topic wandered over to the territory of games. He was discussing his feelings on inFamous versus Prototype and that he in some ways he preferred Prototype because it made you feel more “bad ass.”

His comment struck a chord in me because it reinforced a trend that I’d been noticing in the games designed in the West, as opposed to the games designed in Asia. Of course, both cultures are interested in providing a fun, entertaining experience for the player, but there’s a mindset, likely borne of the cultural differences between the two, that diverges dramatically on how to achieve this. While its true that there’s been a lot of cross over in the pollination of ideas between Eastern and Western game development, it’s also true that these are two very different cultures at work on the same goal, and that cultural difference will have some kind of impact on the products produced. A Western Renaissance painting is not going to look identical to a Japanese Edo period painting, though both may use the same tools and be in the same medium. The same applies to games. And it’s in these differences that we see an interesting reflection of ourselves as a different cultures and different gamers.

The Power Trip

The idea behind gaming in Western development seems to be centered around one primal idea; the power fantasy. This is about enabling the player, giving them access to abilities and experiences far beyond their normal sphere of existence in the interests of allowing them to feel like Superman. It is, in other words, the “Charles Atlas school of videogames,” allowing people who have had sand kicked in their faces to redeem themselves in super-heroic fashion. It is, simply, allowing people to feel powerful. The goal is to give the player the feeling that even if they are bullied, oppressed or somehow contained and restrained in real life, here, in this game, they can cut loose and experience the thrill of being more powerful than everyone else around them. Western games try their damnedest to make sure that the gamer can forget whatever sense of impotency they might feel in their normal lives.

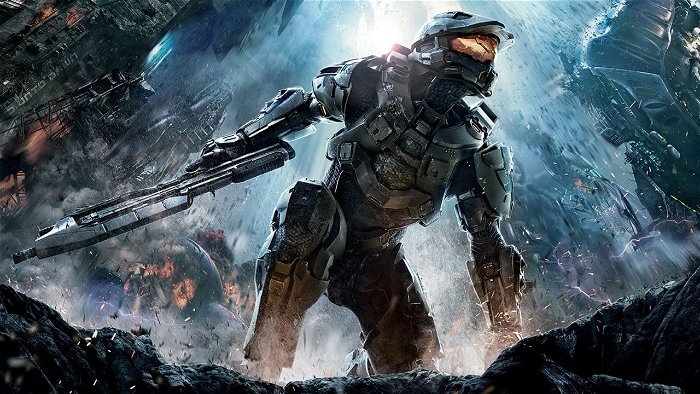

This is a crucial component of many Western games, the supremely powerful “lone wolf.” This is a hero (or occasionally heroine) that often comes out of nowhere, fully formed, incredibly powerful, and is usually the only person capable of solving the problems presented in game, most often accompanied with great praise, admiration and other forms of positive reinforcement from characters populating the world. The most typical example of this is, unsurprisingly, Master Chief from the Halo series, a character that has come to be—for better or worse—a template of Western character design. Master Chief is immediately separated from the rest of the characters in the Halo universe and elevated as exceptional. As the sole survivor of the Earth military’s Spartan program, he has been raised and trained solely for warfare and is cybernetically enhanced, on top of receiving a rare and incredibly robust power battled armor that makes him not just heroic, but super-heroic compared to the standard issue infantry he occasionally fights alongside.

Throughout the course of the Halo series, it is reinforced again and again and again how exceptional Master Chief—and, by extension, YOU, the player—is compared to the people around him. The game constantly reminds the player that he or she is a military miracle, claiming that certain obstacles can only be overcome by Master Chief, allowing him to play a vital role in team operations where the Chief manages to succeed single-handedly, and gaining the fear and recognition of the enemy so that even the Covenant immediately knows Master Chief on sight. At every step of the way, Halo both subtly and forcefully tells players that they are superior, that they can do things no one else can, that their allies respect and admire them while their enemies fear them. The game allows players to enjoy the fantasy that they are the most important person in the universe and no one is comparable to them. It is the ultimate stroking of the ego, and small wonder that, in a culture that prizes fame and adoration above seemingly all else, it would appeal to the fantasy life of such an audience.

Of course, while Master Chief may be the most obvious example of this characteristic in Western games, they are far from the only ones. Sony’s own ambassador to deicide, Kratos from the God of War series is, fittingly, a tragic, lone Greek Superman, in keeping with his mythical inspirations. As with many Greek heroes, he’s a child of the Gods, specifically Zeus. He is an archetypal tragic hero, or perhaps anti-hero, as he pushes forward, single-handedly killing mythical beasts and even Olympian gods. It’s here that we see the Western design philosophy most evident as the original series creator David Jaffe himself said that the game was more about creating a visceral, thrilling sense of power and violence, rather than implementing a complex system of combos and special moves that could only be effectively used through dutiful experimentation and practice. Kratos, like Master Chief is more closely aligned with immediate gratification, granting players quick access to powerful abilities and the fear their enemies. They are the ambassadors of a long line of Western game characters that engage players with the Power Fantasy, such as Alex from Prototype, Cole from inFamous, Nomad from Crysis and, obviously, Batman in Batman: Arkham Asylum.

On the other side of the Pacific, the story is often a little bit different.

The Struggle Against The Odds

Asia, and Japan in particular, have a different culture from the West and that has resulted in a different approach to their priorities. While there are still some universal themes that everyone can relate to such as love, war and even the quest for power, Japanese social outlook and structure have applied a very different filter to how these themes are addressed in games.

As with many Asian societies, the Japanese outlook is very communal, focusing more on the importance of groups and general welfare of the group rather than the well-being of a single individual. This is well reflected in their manga, anime, drama serials and videogames as characters often go to extraordinary lengths to protect or care for members of their community. Shadow of the Colossus for example, is an ambiguous celebration and condemnation of how far one relatively powerless individual is willing to go in order to revive the one he loves. A recurring theme of many Japanese RPGs and action games is the use of strength in order to protect loved ones, as evinced in games like Final Fantasy, Kingdom Hearts, Ico and even Japanese Mafioso, beat ‘em up extravaganza Yakuza. So embedded in Japanese narrative is this motif that it’s become a point of unwelcome cliché, with emo heroes suffering from angst-y frustration because they’re “not strong enough” to protect those that matter. The group plays prominently in such games, particularly in the traditional Japanese RPG that tasks players with cooperating with other party members in order to prevail, a notion taken to an extreme in titles like Konami’s Suikoden JRPG series where the player can eventually recruit up to 108 unique characters to form the basis of some kind of fortress from which military campaigns eventually spring to defend a beleaguered nation. Valkyria Chronicles is another typical example a tight-knit military unit forming relationships, questioning the morality of the war they find themselves in and putting others ahead of themselves in their fight against oppression.

The Japanese focus in gameplay terms seems to be based not on quick gratification empowerment, but gradual mastery. Unlike Jaffe’s God of War for example, games in the same 3rd person action genre such as Devil May Cry and any Japanese fighting game such as the Streetfighter series reward perseverance and practice. The Japanese have a very strong work ethic, believing that putting in the time and practice should yield rewards, and this ethic carries over even into their games. The Devil May Cry series for example, or its recent contemporary, Bayonetta will happily accommodate an unskilled player who “button mashes.” But those that are willing to learn the moves and timing of the intricate combat systems are capable of executing long, complex battle maneuvers that show off uncanny levels of precision and accomplishment. This magnified to an even greater extent in fighting games, where expert level Streetfighter players have the timing of their moves coordinated to individual frames of animation.

This sensibility of “time, discipline and dedication will be rewarded” is most evident in the Japanese RPG. Perhaps it’s merely the Japanese take on escapist fantasy; where the Western developers want players to feel enabled, the Japanese developers want their players to feel like their hard work will always be rewarded. This has resulted in the infamous “grind” that is so symptomatic of many Japanese RPGs and MMORPGs. It is a promise to the player that “We guarantee that you can become powerful, but you must work toward it and it may be tedious.” This same ethic is also evident in the buying habits of the Japanese gaming public. Shooters are an unpopular genre in the country, likely because of the moment by moment gameplay that requires more “twitch-based” reflexes and situational awareness. But a game like Demon’s Souls became popular despite its notorious difficulty, because it could be reasonably overcome by simply taking the time to learn the levels and proper tactics. Knowledge and skill, not speedy reflexes, are the important components of Japanese games. And it is in the blending of these two design philosophies that we see some of the most interesting games of this generation.

Fusion Gaming

It is impossible for these two different gaming cultures to not notice what the other is doing and not be influenced in some way. Japanese games dominated the console gaming scene of the 80s and 90s and are still cornerstones of console design in many ways. But that doesn’t mean the Japanese keep to themselves. For example, one of the ultimate gaming “bad asses” is, in fact a Japanese creation. Solid Snake of the Metal Gear series is the epitome of a lone wolf that empowers the player with his vast array of superior skills against lesser foes, and he’s been doing his thing since the 80s on the MSX2 and NES, a direct inspiration of 80s action heroes from Hollywood. On the other side, BioWare has taken the lessons of Japanese RPGs to heart with games such as the Mass Effect and Dragon Age series that place a special emphasis on bonding and relationships with characters. Ninja Theory, a Western developer that has an appreciation for Japan with the obvious roots of its name, will explore the inter-dependency relationships of pioneering games like Ico in its Enslaved: Odyssey to the West, the game’s inspiration itself taken from the Chinese classic Journey to the West.

This kind of cross-pollination of design ideas is only going to become more prominent as time goes on. Part of this is due to the dominance of the Western audiences as a market, since the combined numbers of Europe and North America dramatically outweigh the market of Japan alone. It forces the Japanese to entertain new philosophies in the interests of selling beyond a relatively small local market. The other part is of course, simply good game design. Good ideas can come from anywhere, and for any country to only look at only its region for design inspiration is ignoring a wealth of opportunity provided an increasingly globalized gaming industry.

This article first appeared in the Oct 2010 issue of CGMagazine.