It’s one of the small oddities of the medium of gaming that one particular genre seems tailor made for interactivity but has had little representation. That genre is cyberpunk, a very specific variant on science fiction settings that came out of the excess and digital revolution of the 80s. It’s a genre that focuses on intrigue, deception, technology and dramatic conflict, but despite that only a few games have ventured into this territory, with the recent Deus Ex: Human Revolution being one latest—and best—ambassadors of the genre to gamers. It’s almost like a clear statement to the gaming community that an important genre, once ignored, is making a comeback to the medium that can do it justice. But why is this genre so compelling? Why is it coming back? To understand these questions, it’s best to start by understanding what, exactly, cyberpunk is.

The World According To Gibson

Often hailed as the “Godfather” of cyberpunk, the genre has as one of its defining creators, the Canadian science fiction author William Gibson. While Gibson can’t be said to have invented the genre from the ground up, he is largely responsible for many of the elements that are regarded as definitive to cyberpunk today. It was his early work in the 80s with short stories such as Burning Chrome and then his landmark “Cyberspace trilogy” of Neuromancer, Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive that laid foundations for the genre.

In terms of theme, William Gibson covered the broad strokes that cyberpunk would concern itself with. There is a sense of near future dystopia to cyberpunk. It’s not that the apocalypse came and went, so much as the world limped on and got a little bit worse with each passing year. Technology has developed unchecked and unfettered by issues of ethics or morality, consumerism has become more prevalent and yet at the same time, poverty and economic class divides have widened. Political power gradually transferred from the federal or national governmental levels to that of multi-national corporations. It is a world where switching jobs to a new company can be as complex, violent and dangerous as a traditional cold war defection from one superpower to another. Espionage has become standard operating procedure for business, and the businesses have a lot more money and authority to exercise it.

It’s ironic that these themes were explored in the 80s, a period of plenty for the West, in particular America, when these ideas seemed far-fetched and unlikely. Fast forward three decades and the prescience of these ideas—such as the erosion of the USA’s importance on the world stage, or the worrying ability of corporate interests to affect government policy—have become everyday concerns that are regularly discussed by just about everyone. Cyberpunk is a world where information is power, and the digital revolution has taken it to such an extreme those that can manipulate the information are the ones in control.

It is a world that has also been largely defined by one seminal movie, Ridley Scott’s 1982 science fiction film Blade Runner. The aesthetic of retro-fitting, of merely adding new layers of architecture, technology and even culture onto an existing structure pervades the entire film. At the time of Blade Runner’s release, Gibson himself was writing Neuromancer and was both elated and horrified at the uncanny resemblance in texture and mood between the science fiction film noir and his own update of the classic, detective noir style for his near-future fiction. Despite the fact that the 80s was one of the most prosperous decades that North America would ever know, the combination of cold war tension and suspicion about “magical” new technologies such as computers and bio-engineering were already planting common seeds of thought in many artists in varying mediums.

And that, of course, also pertains to games.

Welcome To Cyberspace

It should come as no surprise that for those in the gaming industry that ventured into the no man’s land of an untapped genre, a wealth of material lay in wait. From the cyberpunk reliance on technology, to mercenary combat, to ready-made, near apocalyptic settings ruled by evil mega-corporations, these were fertile fields ripe for exploitation and ready to provide players with an intriguing world to interact with.

One of the first efforts to create a cyberpunk game played it safe and went straight to the source. The 1988 adventure game Neuromancer didn’t just pay homage to Gibson’s seminal work, it bought the license and tried to bring the world to life with the crude, low resolution computers that were decades behind the computational powerhouses that Gibson envisioned in his world. After naming the character at your own discretion, you find out he is a “console cowboy,” an underworld hacker. Gradually the puzzles of the real world are negotiated to get back the “deck” (the specialized hacking computer) and the software with which basic hacking is accomplished until better equipment is acquired through means both legal and not. The ultimate goal, as with Neuromancer itself, is to unravel a mystery in cyberspace that involves the wheelings and dealings of various artificial intelligences pursuing their own agendas.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eogpIG53Cis

What made Neuromancer so unique, aside from its adaptation of the famed Gibson novel, was the way it gradually ramped up the access to technology that players had. What starts as a simple adventure game with players fetching various items at the request of non-player characters turns into the quest for network addresses and passwords for elementary electronic intrusion. Eventually, when the player finally gets access to a cyberspace-compliant deck, passwords and addresses give way to attack programs and digital combat with ICE—intrusion countermeasures electronics—and the AIs that devise them. It is also one of the rare cyberpunk games that takes a pure, adventure approach to the genre, rather the other titles that make combat a mainstay.

But if Neuromancer the game covers the groundwork of hacking, then the next large entry for cyberpunk gaming tackled the issues of corporations as the new political power. Literally. In 1993, Peter Molyneux, riding high on Bullfrog Productions previous hits Populous and Powermonger debuted the futuristic, multi-platform title Syndicate. The premise puts players in a world where national governments have broken down and the various regions of the world are now controlled by “syndicates,” a fusion of a large corporate entity with organized crime group. The player is at the head of the newest syndicate, and from humble beginnings, controlling four cyborg warriors using turn-based strategy mechanics, goes on to eliminate rivals, expand territory and dominate the globe.

With Syndicate, players were introduced to a more strategic game, one that leveraged heavily on Molyneux’s own experience with the “God Game” genre he defined in Populous. Syndicate went in the opposite direction of Neuromancer, ignoring the individual in favour of a larger stage with greater focus. It’s also brutally Machiavellian in practice, regularly presenting players with opportunities to sacrifice—and in some cases brainwash—civilians as fodder in order to achieve objectives. Syndicate puts players in a position where the end justifies the means. It gave players an understanding of the motivations that occur in a cyberpunk world where people with power have no responsibility to anything except profit and personal advancement. While no one is going to actually condone Syndicate’s methods, it makes it easier to understand the motivations of an authority that views people as little more than chess pieces used to “win” the game.

From Syndicate in 1993 to Shadowrun (in 1993 for the SNES and 1994 for the Genesis) cyberpunk takes an interesting turn when it moves into the genre of the RPG. The Genesis version in particular, developed by BlueSky Software, provides a varied experience that manages to stay surprisingly faithful to the original source material. Shadowrun is an interesting concept because its roots lie in a traditional, pen and paper role-playing of the same name released by FASA in 1989. Unlike “vanilla” cyberpunk, which was squarely in the speculative science-fiction department, Shadowrun mixed things up by postulating that not only was the world bleak, futuristic and dystopian, it also had elves, orcs, dragons and magic users living and fighting alongside its hackers and cyborg soldiers. Ironically, according to Shadowrun lore, in the year 2011, magic inexplicably began to function once more, and dormant races like elves and orcs that had been absorbed into humanity, reasserted themselves, while other species, like dragons, awoke from their hidden chambers of slumber. Fast forward 63 years later to the year 2074 and the stage is set for Shadowrun adventures.

The Genesis version of Shadowrun is an action-RPG that focuses on Joshua, a man with the classic dilemma of having his brother killed, putting him into revenge mode. The game takes place in a futuristic Seattle, as Joshua arrives and performs basic “Shadowruns” or quasi-legal activities, in order to track down information on the Shadowrun job that got his brother killed. Players could choose between basic character configurations for combat, hacking and magic, and then went on to both develop their character and explore a world in which they could perform straight combat jobs for hire, or, if they so chose, hack into systems to steal illicit information. For its time, Shadowrun provided the broadest, most complete interactive cyberpunk experience, and it remained so for a few years until the inevitable heavy hitter arrived.

In 1997, Westwood Studios, usually better known for their work on the infamous Command & Conquer real-time strategy series, surprised everyone with the release of not just an adventure game, but one based on Blade Runner. By this point in time, Blade Runner had rapidly risen from its humble beginnings as a theatrical failure of the early 80s to a highly regarded cinematic experience with the respect of both the audiences and the critics. Blade Runner the adventure game, was, unfortunately doomed to a similar fate, experimenting with both narrative and technological mechanisms that may have been too far ahead of their time, only to gain more recognition in later years.

Rather than put players once again in the shoes of the film’s main character, Deckard, the Blade Runner game focuses on Ray McCoy, a Blade Runner who is tasked with a similar mission. He is also on the trail of a different set of Replicants to kill, and his mission is running concurrently with Deckard’s, with numerous references to that more famous Blade Runner dropped throughout the course of the game as the two missions narrowly miss each other. While the mechanics of the game were the familiar point and click interface that was well understood at this time, the game pushed the technology envelope by using a 3D technology known as voxels. Voxels would eventually lose out in the war for 3D graphics to the polygon that is the mainstay today, but it had the virtue of not requiring some kind of hardware acceleration like today’s graphic cards. It also took the difficult high road of providing a large amount of choice to the player, with 12 possible endings available depending on actions taken throughout the course of the game. Like Shadowrun before it, it gave players a glimpse of gameplay where the setting was complex and choice was always available, something that would see even more fruition in later years.

It was when the original Deus Ex—developed by Ion Storm and directed by none other than Warren Spector—arrived in the summer of 2000, that players discovered a world in which abundant choice was not just a moral quandary, but a consequence of actual gameplay. As JC Denton, players controlled a nano-augmented agent of United Nations Anti-Terrorist Coalition. UNATCO is dedicated to preserving order in the face of a rash of terrorist activity that arose when it became clear a new plague sweeping across the world had a cure, but the cure itself was expensive and valuable, being reserved only for upper class of society. As Denton goes about his job he begins to uncover a conspiracy that rises up to the highest levels of corporate and government authority.

Deus Ex was an important game, not just for introducing a generation of gamers to a vast world of conspiracy theory, but for presenting a compelling environment where players had multiple solutions to problems. For those that didn’t enjoy gun-based combat, it was possible to pick locks, or hack computers, or even employ stealth tactics to bypass security or remain unseen. It also brought an incredibly complex story along with it that touched on everything in conspiracy mythology from Area 51 to the Illuminati. Like the genre itself, the Deus Ex game was a complex one that addressed many concerns, from the abuse of power by authority to the sheer variety of ways that a problem could be resolved, whether it was through violence, stealth, or technological prowess. It was a game that resonated heavily with audiences of the time by expanding the possibilities of gaming as well as bringing new layers of complexity to narrative in gaming.

Since then, Deus Ex has influenced the development of many games in its wake, but cyberpunk as a genre fell out of popularity in many media including games. It seemed the near future had lost its appeal with audiences who either preferred the contemporary settings of Modern Warfare or the far-flung future of Halo and Mass Effect. It would be many years before cyberpunk would make a high-profile return, but it happened.

The Present & The Future

Deus Ex: Human Revolution is a surprising and triumphant return for the genre. It follows its predecessor closely, providing numerous choices in play, while at the same time taking advantage of the advances in technology to present a richer, deeper world. The graphics in particular are evidence of a team at Eidos Montreal that is well aware of the roots of the game, with art direction that looks like it walked off the set of Blade Runner. It also touches on relevant themes that have raised more concern as time and technology have advanced. Deus Ex explores the notions of cybernetic implants and the implications it has on a world where people with money can not just correct physical defects, but even enhance natural abilities far beyond those of natural humans. Where does one draw the line when corporations promise a faster, better, smarter person… but only to those with a sizable income?

Perhaps it is because of the uncertain times the world finds itself in that the questions and ambiguity of cyberpunk have resurfaced. With recent troubles such as the collapse of the American economy placed largely on the shoulders of big business, the mistrust of corporations has grown to new highs. As the internet has entrenched itself in the lifestyle of most people around the world, the concerns about technology, privacy and information is once again a focus. Recent conflicts all across the globe have reminded us that nations go to war for reasons not necessarily in the best interests of their people but rather for profit and resource control.

And surprisingly, this return to cyberpunk in gaming is coming faster than people had anticipated. After a lot of leaks with no comment, Electronic Arts has finally confirmed that a new Syndicate game is on the way in early 2012. Like X-Com, the developer—in this case Starbreeze—is eschewing the original strategy genre that Syndicate was created in, and is turning it into a co-op first person shooter. While it’s not exactly the return that people had been expecting, Deus Ex: Human Revolution has already shown that contemporary gaming is still ready for a meaty, cyberpunk experience. With any luck the new Syndicate game will provide just that, despite its new direction.

Cyberpunk Movies

If you’re looking to see what all the cyberpunk madness is about, here’s a quick listing of some movies that capture the essence of the genre.

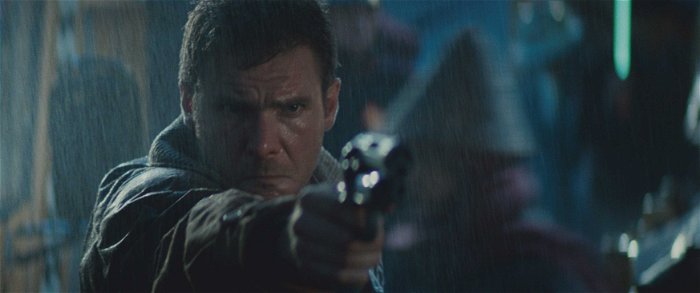

Blade Runner

This is pretty much the foundation of cyberpunk in cinema. Half science-fiction, half film-noir, Blade Runner is the mad fusion of a Philip K. Dick novel (in this case, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep) with the astounding cinematography and art direction of Ridley Scott. Harrison Ford plays a retired detective brought back into service for a final mission. He must track down artificially created humans that are physically superior in every way except for their three year life-span. Questions of ethics, humanity and identity all come into play in this seminal film that defined the look of an entire genre and influenced a generation of film makers.

Johnny Mnemonic

This movie is an automatic candidate for “cyberpunkiness” if for no other reason than it’s adapted from the William Gibson short story of the same name. In this case, Johnny is a living “memory stick,” who is paid to store sensitive digital information that needs to be kept off the grid. Things go horribly awry when extremely sensitive data is tracked to down to him and people start trying to kill him. 90s style virtual reality interfaces make an appearance as cyberspace, and Dolph Lundgren makes a surprise turn in this unique, but ultimately uneven treatment of one of cyberpunk’s foundation stories.

Strange Days

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow, this 1995 film takes the basic notion of Gibson’s “Sim-Stim” or simulated stimulation, and turns it into the basis of an ugly struggle during the 1999-2000 New Year’s eve. Called a SQUID (super conducting quantum interference device), the technology allows “viewers” to experience every sensation of the person recording the experience. When a black market SQUID dealer—who usually dabbles in porn—gets a hold of a recording showing a woman being killed by cops, a conspiracy unfolds that has the dealer (Lenny Nero, as played by Ralph Fiennes) fighting for both his life and the truth.

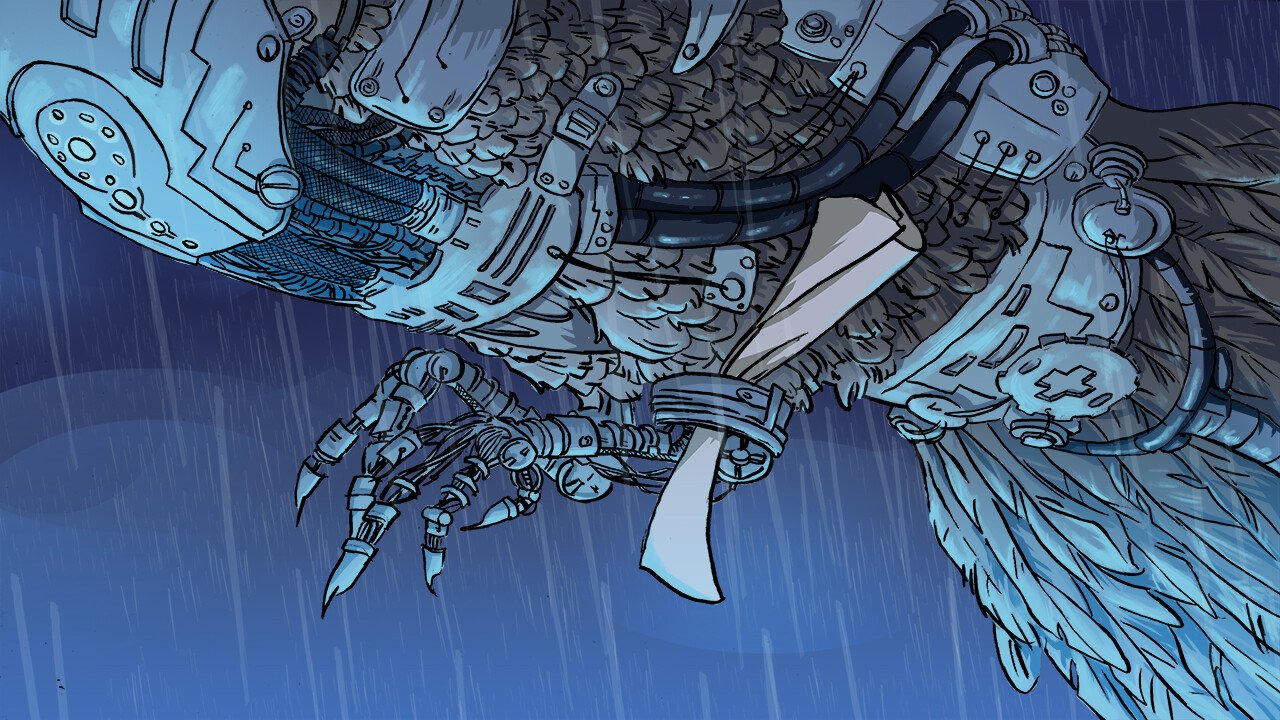

Cyberpunk Comics

It’s not just movies that are fascinated by dystopic, high-tech futures. Plenty of comics have explored this territory as well.

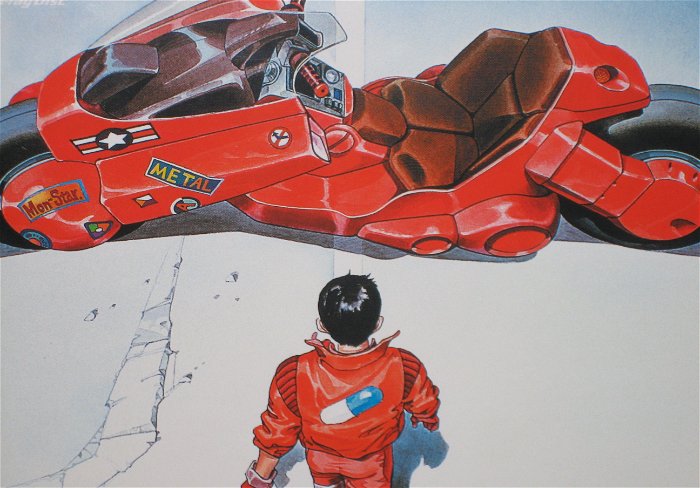

Akira

Another one of the heavy hitters in the genre, Katsuhiro Otomo’s massive work focuses on a motorcycle gang, and what happens when one of their own is turned into a homicidal psychic psychopath. Technology, conspiracy, a rebellious punk sensibility and some dazzling speculation into the fate of a future Tokyo all give Akira a tremendous weight and scope that few stories have dared to match. Otomo’s ridiculously detailed art is another high point of the series, with an attention to urban detail that borders on obsessive. Although Akira was also turned into a stunning movie—which was also directed by Otomo—the 2+ hour viewing experience obviously lacks the substance of a manga that is 2000 pages in length.

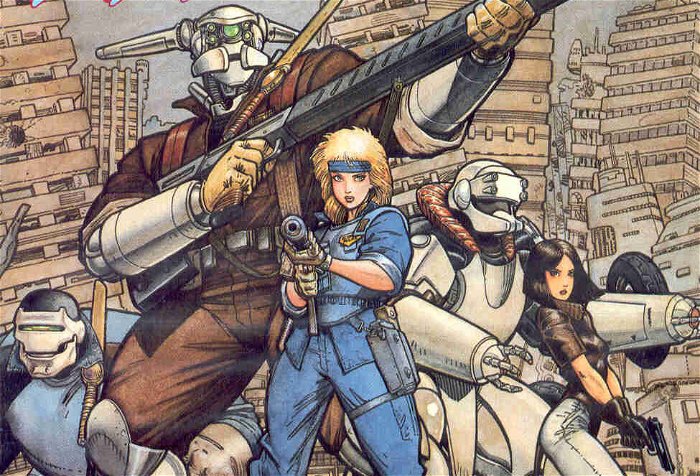

Appleseed

Another import from Japan, Appleseed is the early work of Masamune Shirow who would go on to create other notable cyberpunk works such as Ghost in the Shell. Appleseed is a complex manga that addresses themes of genetic engineering, cybernetic augmentation, and the concept of government in a post-apocalyptic world. The story is seen through the eyes of Deunan Knute, a female SWAT officer partnered with a combat cyborg known as Briareos. After being rescued from their scavenger lifestyle out in the wastelands of a post-World War III landscape, they take up citizenship in Olympus. This new city was an advanced project in the extensive use of bioroids, or genetically engineered humans. It now acts as the seat of government in the devastated new world, but there are many nations unhappy about this new transition of power. Deunan and her partner get caught in the crossfire.

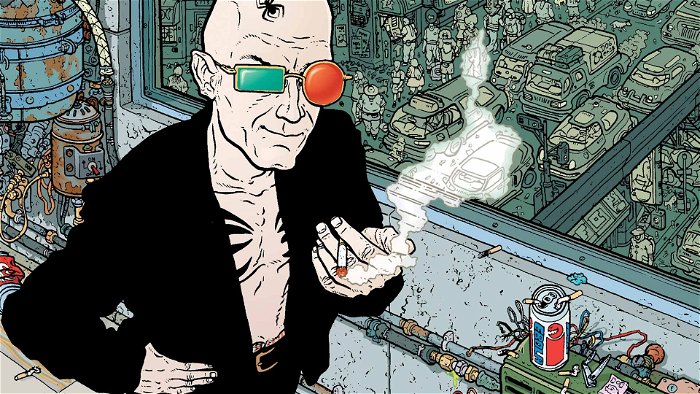

Transmetropolitan

Transmetropolitan is another notch on the demented belt of Warren Ellis. Where the previous two works were Japanese, grounded in a lot of “hard” science and pushed their speculations in imaginative but relatively conservative directions, Warren Ellis’ work is “gonzo,” going as far out as it possibly can with the most outrageous concepts. The protagonist, Spider Jerusalem, is a journalist living and working in a far flung, futuristic city where everything from suspended animation to total consciousness conversion into a nano-cloud is possible. It’s in this world that Spider negotiates the often confusing culture of accelerated change and ultimately battles corruption both corporate and government.

This article originally ran in the November 2011 issue of CGM.