I own a DVD compilation that contains 50 low-budget science fiction and horror movies spread out over five or six discs. These movies range from 1950s and early 1960s black and white thrillers to 70s and 80s productions with quality so bad that it can be next to impossible to pick out what is actually occurring in a given scene. Despite the uneven quality, after a friend gave me this collection of movies as a Christmas gift I was so excited that, over the years, I’ve actually watched the majority of them.

Each of the films neatly fits into the categories of B movie and/or camp. These terms, as most of us know, have far more to do with quality and tone than anything else. Just because my collection is comprised of sci-fi and horror, the genre of the movies is pretty much incidental (The Room is a great example of a B drama). Quality B movies are united only by being the kind of entertainment that is so bad it spirals back around on itself to become something like good again.

It’s probably the cynic in me, but these are some of my favourite works of art. Laughing at bad line readings, gaping plot holes and trite storylines is a whole lot of fun (especially with a friend) and, luckily enough, the pleasure of B entertainment extends past film and into videogames.

Just Plain Bad

First things first: not every bad game is worth playing. There’s a kind of metric that has to be applied to all kinds of B media, whether film or videogame, before something bad can be considered redeemable: it has to be technically proficient enough to be played/watched without the audience being constantly annoyed by a lack of function.

What this means is that, when watching a B movie it’s usually not the good kind of bad if, say, the entire film is poorly lit and it’s difficult to see any of what is going on in frame. A videogame that controls poorly, has progress-blocking glitches or is otherwise broken in some fundamental, technical sense falls into this category as well. Any entertainment that makes its viewer fight with it just to try to get something out of the experience is definitely not worth the time.

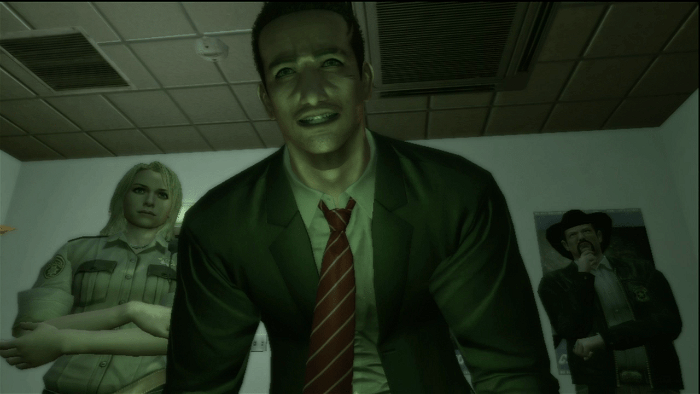

Many would argue that Swery65’s cult classic Deadly Premonition belongs to this category. Premonition controls awkwardly, is packed with frustrating design decisions, is often glitchy and flirts with outright plagiarism in its homage to Twin Peaks (see if this sounds familiar: in the game an eccentric FBI agent arrives in town, speaks every observation aloud to an unknown third party when alone and attempts to solve the murder of a young woman with clues left underneath her fingernails before getting caught up in a supernatural mystery). It is a game that challenges the player to enjoy it, but is still has enough merit to position itself a notch above other time-wasters.

Something like The Cursed Crusade — a co-op hack and slash title from Kylotonn — is a better fit for the category of unredeemable games. Awful writing and voice acting make it a prime candidate as a B game, but the repetitive gameplay, frustratingly poor mechanics and sloppy technical presentation keep it from being in any way enjoyable. It misses earning even the dubious honour of being called a B game because it’s, in the end, just plain broken.

See also: quickly produced “shovelware” games; Superman 64; E.T. the Extraterrestrial

Light and Breezy Bad

Videogames — even excellent videogames — are perfectly capable of being full of ridiculous trappings. Because the medium is built on the foundation of satisfying and enjoyable game mechanics, the writing often takes a backseat. The common design approach — gameplay first, everything else after — often leads to great games with shaky production qualities or inadvertently funny narratives. This kind of design malfunction provides the greatest wealth of B games.

When the Resident Evil series started it gave players a genuinely frightening setting and a unique blend of action and puzzle solving. Just the same, every well-executed moment that burned itself into the audience’s memory (the creeping terror of discovering that first zombie gnawing away at a corpse, the heart-stopping shock of a mutant dog bursting through a hallway window) was matched with others that stuck in the mind for the wrong reasons. Resident Evil’s clunky writing, theatre student drop-out FMV intro and beautifully sincere but awful voice acting create something like the Platonic ideal of a B game. Wesker and Barry’s best lines, whether they’re talking “Jill sandwiches,” describing their devious endgame plots or offering lockpicks to the “master of unlocking,” may linger on far longer than the excellent sound design and atmosphere.

As mentioned before, these presentational failures don’t necessarily have to work against enjoying the game. Part of the fun (for me at least) in playing something like Resident Evil is in giggling at the unbelievably flat voice acting or goofy dialogue writing. Sure, this sort of thing breaks some of the game’s tension, but it also provides a different kind of satisfaction. Would pumping quarters into a House of the Dead 2 arcade cabinet still be as much fun if the voice acting was actually competent? Probably not. It’s the hammy readings and inexplicable plotline that makes the game what it is: a fairly standard lightgun shooter that elevates itself by being completely ridiculous. Resident Evil shares the same honour, an innovative game that lives on in infamy for reasons beyond its groundbreaking take on interactive horror.

More recent titles like Binary Domain have continued this trend, offering a solid set of gameplay mechanics that may have lead to a forgettable game, but wrapping them in up in enough campy silliness (a scarf-wearing robot with a French accent; the psychotic facial and verbal expressions of the hilariously named Big Bo) that the whole affair turns into a memorable piece of entertainment — in short, a great B game.

See also: badly translated localizations; early to mid-90s FMV games; Devil May Cry; House of the Dead; 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand

Self Serious Bad

Even videogames developed by studios that take great care to craft interesting stories can become B-level entertainment. In these cases, well-intentioned writers and generally competent voice actors come together to create something unique: self serious games that are funny because they don’t know they’re being funny.

Probably the most notable examples of this type of B game come from the Final Fantasy series. As much as they’re held up as great videogames by their fans, Final Fantasy stories are almost always packed to the brim with melodrama, straight-faced narrative convolution and ludicrous character/enemy designs. The most celebrated entry in the franchise — Final Fantasy VII — revolves around super soldiers, talking lion creatures, alien monsters and pseudo-spiritual nonsense involving “Lifestreams,” after all.

Metal Gear Solid, a series that I love, but cannot ever try to defend, fits into this category as well. Its blend of real-world political commentary is potent, but colouring the whole affair with ghosts, personality altering arm grafts and vampire men makes it difficult to take everything as seriously as the creators would probably like. It’s this same blend of ludicrous and believable elements that makes another long-running videogame series such a delight. Aspects of the Yakuza series suggest that the games’ developers are aware of their ridiculousness (fist-fighting tigers and gaining power-ups through cellphone snapshots), but the gangsters that populate the fictional setting of Kamurocho are wholly sincere in their Mafioso infighting and intrigues. Both Metal Gear Solid and Yakuza are wonderful for this reason: they are game series so campy, but so genuine in their approach, that it’s impossible not to get sucked into their overblown narratives even as nearly every scene invokes a smirk or giggle.

It doesn’t hurt that most self serious “bad” games approach their game mechanics and production values with as much care as their hokey drama. While it can be fun to listen to poor voice acting or marvel at boneheaded writing, the more polished presentation of the games mentioned above makes for a far more enjoyable B game experience than the less impressively designed titles mentioned above. When a B game can involve the player by presenting a story that is at least competently put together it only becomes more fun to see it blasted apart by baffling design choices later on.

See also: the vast majority of fantasy-themed games; Heavy Rain; Resident Evil 5

A Knowing Bad

Many self-aware creators know that the premises they want to explore in the videogames they develop are inherently silly. This doesn’t always mean that they decide not to go forward with them. Instead, many developers take a satirical approach to their subject matter, creating videogames that are in on the joke right alongside their players.

Suda51 (Goichi Suda) has firmly established himself as the king of the knowingly “bad” B game. His No More Heroes, Shadows of the Damned and Lollipop Chainsaw all revel in videogame clichés, featuring characters who seem as aware of the absurdity of themselves and the worlds they inhabit as the player is. The over the top dialogue and design in these games is reminiscent of the B games mentioned above, but Suda’s titles are differentiated by their willingness to riff on their own absurdity. Resident Evil 4, a game that revitalized the badly aging franchise mentioned above, may or may not have been aware of its own silliness as well. While there really shouldn’t be any argument as to whether or not it qualifies as a B game — the clueless dialogue and hammy character design confirm its place in this “genre” — it’s difficult to tell whether Capcom, Resident Evil 4’s developer, is laughing along with its players when it introduces its maniacal, Napoleon-hatted little boy antagonist or opens its story with a former police officer/new special agent attempting to rescue the President’s daughter from a sleepy Spanish village. Most players tend to take the same approach I would lean toward, though. The overblown nature of the whole game suggests that Resident Evil 4’s developers knew full well just how ludicrous their title was.

These games drift further into the realm of satire than may be appropriate when classifying B games, but, much like how Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez have revitalized the B movie while still being fully aware of the type of films they’re creating, these titles provide much of the same enjoyment as their less self-conscious peers.

See also: Eat Lead: The Return of Matt Hazard; House of the Dead: Overkill; Bulletstorm; possibly the Dead Rising games

As the medium of videogames matures, attracting increasingly talented and thoughtful creators, the B game may very well fall into the niche place that B movies currently occupy in the cultural landscape, but they’ll never disappear completely. As long as we have overly pretentious, clueless or just plain hammy game developers we will also have plenty of games to place alongside bargain bin horror and sci-fi films on the shelf — to give interested audiences a chance to create their own little Mystery Science Theatre 3000 programs with their friends.

I love well written, well acted and generally well constructed games, but they don’t have to be the only ones I play. There’s a wealth of campy B games out there — treasure troves of unintentional humour just waiting to be discovered by players willing to take a chance at trying them. In an industry that sees developers constantly attempting to create the next big thing and expand the borders of the medium, it seems worth looking at where games stumble and to make sure that those titles aren’t viewed as unworthy of a player’s time. That, to me, makes B games something worth celebrating.

This article originally appeared in CGM’s October 2012 issue.