We’re entering a bold and strange time for gaming. In one way, gaming has become more structured, regimented and uninspired than ever, with the advent of annual, “AAA” titles that cost so much money to make that risk-taking is no longer an option. On the other hand, the advent of the indie gaming community—and perhaps even more importantly, the adoption of investment entities like Kickstarter—have made it possible for concepts that don’t have multi-million dollar profit potential to still get made.

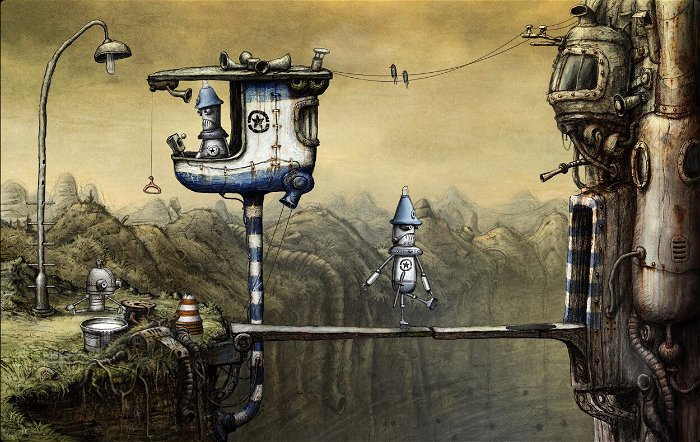

These factors bring us, quite surprisingly, to the humble adventure game. It was a genre that once ruled the PC roost when nerds were the primary users of the platform. The advance of the graphics card and the mass acceptance of the technology by society at large pushed the genre out of the limelight and into the fringe. In recent years however, the genre has been enjoying something of a resurgence. Thanks to new methods of digital delivery such as Steam, the Xbox Live Marketplace and PlayStation Network, these smaller, less budget oriented titles are still able to find an audience with a game like Machinarium slowly but steadily drawing attention to itself while developers such as Telltale Games have surprised everyone with the quality and popularity of The Walking Dead series that they’ve put on any viable platform.

This brings us to the question, “If the adventure game has a second chance to get back more of the audience, what kind of chance should it take?”

The Veterans

The first and perhaps most encouraging sign of the genre’s reviving fortunes comes in the form of old names from the past that the fans haven’t forgotten. Jane Jensen, Al Lowe, Scott Murphy & Mark Crowe, Charles Cecil and, of course, Tim Schafer, are making adventure games again. It was Schafer, earlier in the year with his amazing success at the Kickstarter website for “crowd-sourced investment” that paved the way for the others to follow. Now all of these favourite creators—mostly refugees from the old publishing house Sierra Entertainment—have gone directly to the fans to tell them, “If you give us the money we will make this game for you,” and the crowds have responded in epic fashion, meeting their relatively modest budgetary requirements in short order.

This is great news for everyone that is an established fan of the genre. Tim Schafer is probably the most well known of these developers thanks to his PR friendly persona, and the continuing nostalgia people have for Secret of Monkey Island and Psychonauts. But Jane Jensen is best known for the Gabriel Knight series while Al Lowe made sex comedies viable on PCs thanks to Leisure Suit Larry. The team of Scott Murphy and Mark Crowe brought science fiction into the mix with Space Quest and now even Broken Sword is making a return thanks to Charles Cecil securing over $700,000 USD of the $400,000 he initially asked for to make a sequel.

All of this goes to show that the fans are there, and they remember quite fondly the quality of these games from yesteryear. They were just ignored by the publishers who felt they didn’t exist in sufficient numbers to justify the expense of a multi-million dollar game development project. This, in one sense, is the big “weakness” of publishers this size; as a big publisher, they focus on big projects with big budgets that require big audiences to justify the expense. The adventure game can still succeed and be profitable, but only at a lower budget to offset its smaller audience. Schafer, Cecil, Jensen and all the rest have realized this and gone directly to the people who actually want these products to get their help. It’s clearly a move that, in an Internet world, has succeeded.

These adventure games however, are going to be “safe.” They are going to be familiar point and click style experiences, some even still using traditional 2D pixel art, with dialogue and characterization from beloved, familiar names. These adventure games, in other words, will be comfort food, reminding adults of a time when they were kids, parked in front of their computers, playing with low res graphics that invited them to let their imaginations soar. These are adventure games that provide new nostalgia.

The New Way To Adventure

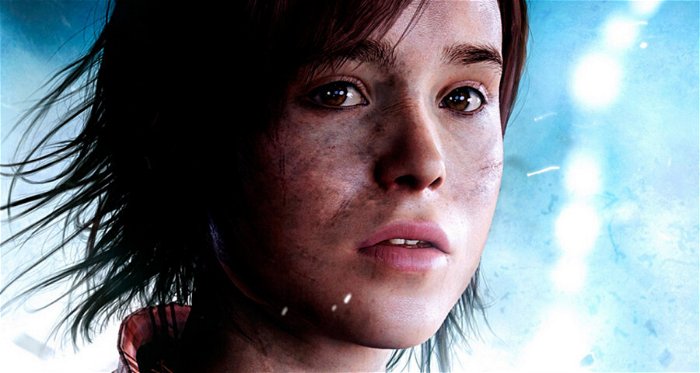

For a peek into what adventure games can offer us in the future, there are really two developers fans of the genre should be looking at. Quantic Dream and Telltale Games. With Heavy Rain and the upcoming Beyond: Two Souls, Quantic Dream has bucked the odds and created a unique series of games that qualify as “AAA” adventure games seemingly through process of elimination alone. They’re definitely not action games, first person shooters or role-playing games in the traditional sense. So these cinematic experiences, with their reliance on narrative, character development, puzzle solving and inventory management must be adventure games, although of a kind not quite seen before. One of the most radical additions that David Cage brings to genre with these games is the idea of a story that “doesn’t stop.” Even if a player fails at a present challenge—sometimes even resulting in the death of a controllable character—the game simply takes these events into account and adjusts accordingly for a new series of choices and endings based on these new conditions. Cage took the idea of cinematic action and applied it to every aspect of Heavy Rain, using an elaborate, all-encompassing Quick Time Event control system to handle every action in the game except general movement. Despite all these changes, underneath the polished exterior is a system of mechanics that is, at heart, still about puzzle solving to advance a story. The difference now is that the puzzle solving—at least in Heavy Rain—takes on new horrific forms like limb amputation in addition to more staid activities like crime scene investigation. It’s not so much that Cage has changed the mechanics of adventure games, so much as pushed the perceptions of applying those mechanics.

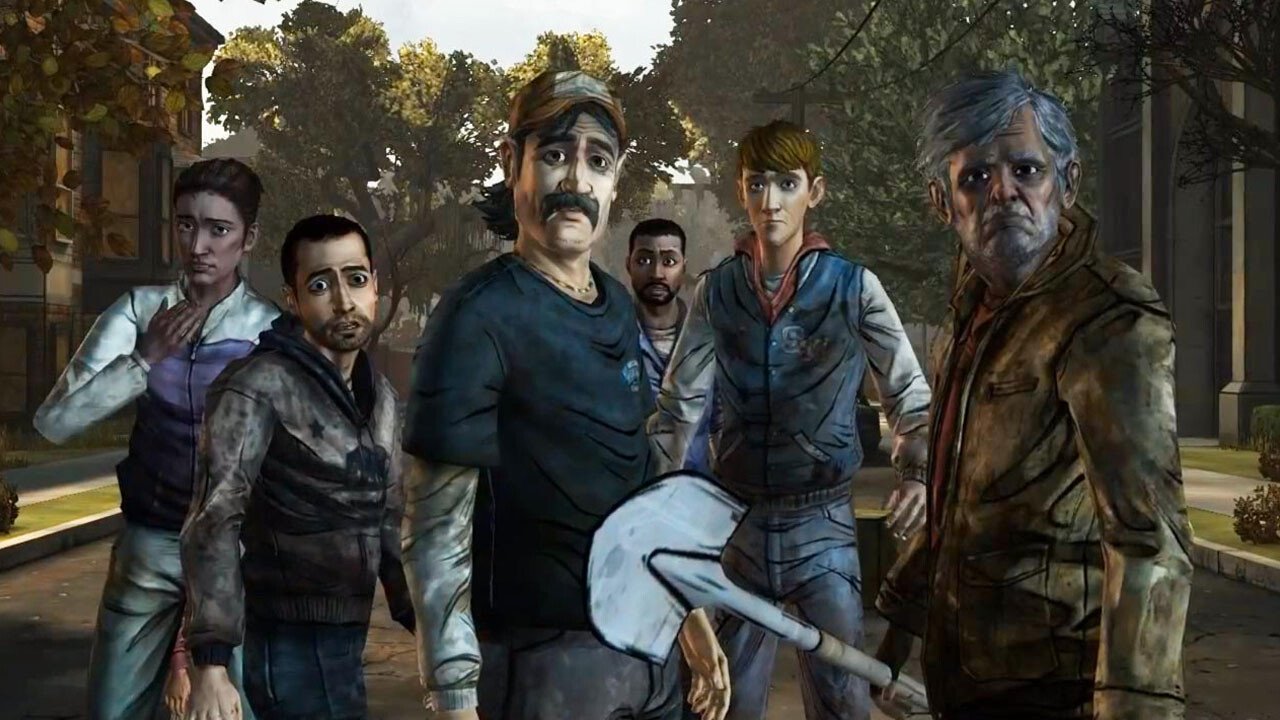

Where David Cage aspires to giving the adventure game a cinematic sheen, Telltale Games has gone a slightly different route; mimicking serial episodic television or comics. The form had been successfully executed in previous, more comedic efforts such as the beloved Sam & Max series, but beyond the episodic format, the games played and felt very much like traditional point and click adventure games. This changed radically with the pioneering—but ultimately failed—Jurassic Park game Telltale released, and reached a successful level of evolution with The Walking Dead series that is now awaiting its fifth and final episode.

With The Walking Dead, Telltale not only managed the rare feat of making a game that didn’t embarrass its source material, they changed the way adventure games play and feel. In fact they did it to such a degree that The Walking Dead may very well be the most successful adventure game on the market today. It’s widely available on PC, console and mobile platforms and at every turn it is garnering rave reviews and strong word of mouth. Telltale succeeded by looking at some of the innovations that have occurred in other genres and using them to buck tradition within their own. The use of a “karmic metre” with regards to characters remembering how you treated them and responding accordingly at a later date has clear influences in BioWare games. From Knights of the Old Republic to Mass Effect, players have had the opportunity to interact with characters in conversation or other situations, and make choices that those characters may or may not approve of. That later shift in attitude could result in new repercussions later in the plot of a typical BioWare game and this same concept has worked brilliantly within The Walking Dead’s occasionally tense confrontations among characters. Another twist to this mechanic is that responses are now timed, lending a tension to heated arguments that even the Mass Effect series lacks. In similar fashion to Quantic Dream, Telltale has now also adopted the much maligned Quick Time Event and given it a more acceptable home in a genre that normally relegates actions to cutscenes or even eschews them entirely. In games such as God of War or even Tomb Raider players would decide having certain actions taken out of their control and put into a cinematic with timed button presses. But in a genre that has almost no action to begin with, these simpler mechanics add a new level of easily accessible excitement and tension to what has traditionally been a much more cerebral, methodical affair.

And finally, let’s not forget the importance of pacing. The nature of episodic television in recent years has jumped dramatically in quality. Everything from the adaptation of Game of Thrones to hit series like Lost have taught valuable lessons in telling a story that ends in such a way that it leaves the audience wanting more. The Walking Dead has learned those lessons leaving its players with the novel experience of thinking “I can wait to see what happens next.”

This article originally appeared in CGM October 2012.