Taking a break from his usual pet themes of having gangsters kill each other or Oscar-baiting with Leonardo DiCaprio, Martin Scorsese has gone and made a children’s fantasy film in 3D called Hugo. That’s certainly as wild of a career jump as George W. Bush suddenly deciding to teach children how to read atheist literature, but somehow the master filmmaker manages to fare quite well with material that might seemed more suited to fellow 70s movie brat Steven Spielberg. Even though the lavish, heightened, Paris production lacks the hyper-violent New York realism that made the director’s name, the project does feel oddly personal for the filmmaker. In many ways, it’s Scorsese’s love letter to the powerful sense of fantasy and escape offered by the movies, and given that there’s no bigger cinephile than motor-mouthed Marty, he’s definitely the man for the job.

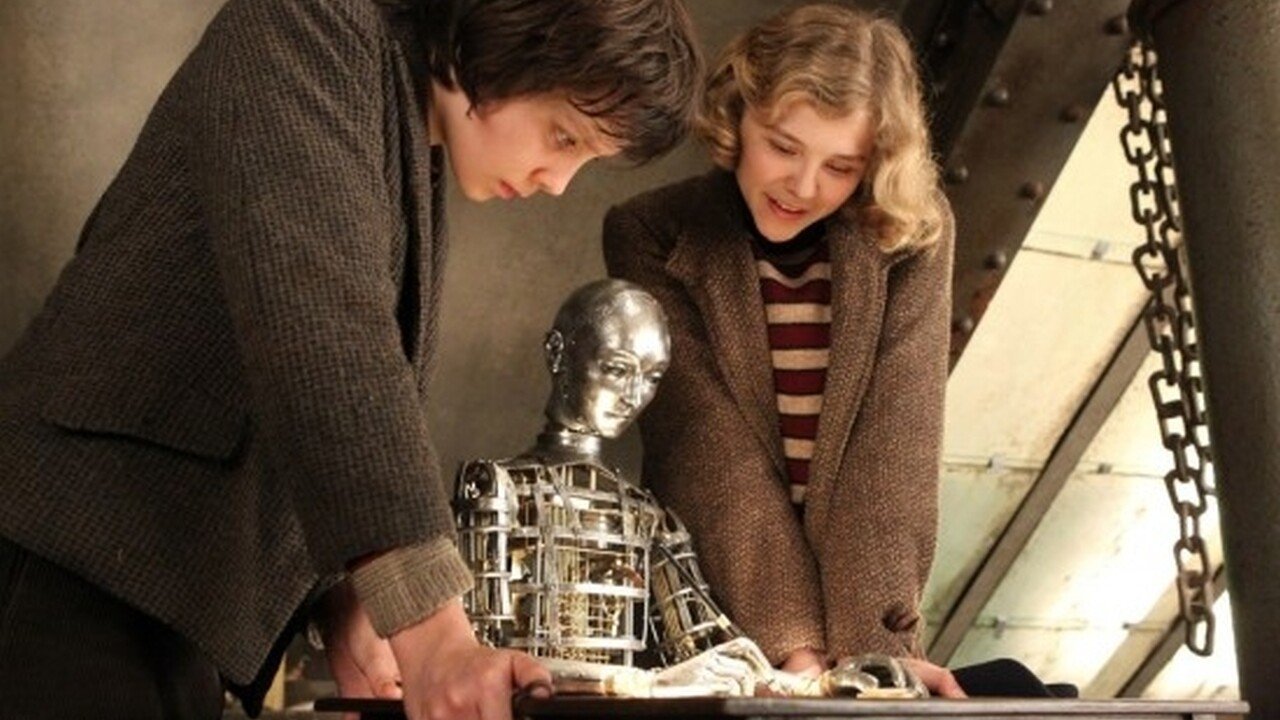

Based on Brian Selznick’s well-regarded illustrated novel The Invention Of Hugo Cabret, the film opens like Harry Potter-style fantasy. Scorsese flies his 3D camera down from an aerial snowglobe view of Paris to find an orphaned boy named Hugo (Asa Butterfield) working inside the clock of a train station. He’s been hiding there and working for his drunken uncle ever since his father’s death, constantly avoiding the slapstick station inspector (hilariously played by Borat himself, Sacha Baron Cohen). The only thing Hugo lives for is trying to fix the strange clockwork automaton man that he discovered with his father. One day he befriends a young girl (Kick Ass’ Chloe Grace Moretz in a rare C-bomb free role) whose adopted father (Ben Kingsley) is a bitter toyshop owner at the train station. Gradually they discover that the old man is actually pioneering silent movie legend George Méliès, who was responsible for the 1902 sci-fi film school classic A Voyage To The Moon. Together the remind the old man of his magical past and rediscover his extraordinary legacy that continues to this day.

Hugo both is and isn’t a children’s fantasy. The film certainly starts off in that mold, with an Oliver Twist-esque orphan in an exaggerated lyrical world with a clockwork robot. Then, as the story evolves, it turns into semi-fictionalized history-lesson about the great George Méliès. Scorsese never drops his heightened whimsical tone thoughout, and in an strange way that’s appropriate. More than anything else, Hugo is a feature length ode to movie magic, as well as a beautiful example of the form. Trained as a magician, Méliès was one of cinema’s first fantasists, and Scorsese lovingly recreates the master’s groundbreaking work, while letting some of that style seep into his own. Considering that the movie is about the enduring power of old-fashioned celluloid entertainment, it’s undeniably bizarre that it’s been shot in digital 3D (which Scorsese uses effectively, as should be expected from the visual genius). Part of me wishes it had been made with the same sort of 35mm film that the story practically fetishizes, yet at the same time with the movie being about an important technical innovator, it kind of works.

Despite the subject matter being so far outside of Scorsese’a comfort zone, he manages to capture the style and tone of the material perfectly. His sepia tone visuals and gorgeously computer-tinted Technicolor flashbacks are absolutely beautiful and as always, he works wonders with his cast. The young actors nail their roles perfectly, while Kingsley plays a wonderfully stern and difficult Méliès and Sacha Baron Cohen improvs up a storm of hysterical comedic relief. Obviously, it would be nice if Scorsese was still exploring the darkest aspects of human nature with unflinching realism as he did in the 70s, but clearly that time in his career is over. Over the last decade, the director has become somewhat of a studio hired hand (as he always wanted to be) and he’s gotten proficient at mainstream entertainment. Hugo is probably his sweetest and most openly crowd-pleasing effort to date, and also feels like his best movie in years because of its oddly personal nature for the cinema historian film preservation activist.

Scorsese was a sheltered child whose primary source of joy and escape came from the movies. Hugo is openly about the medium’s unique power and tells the story of a young boy whose life is forever changed and improved by the movies. Scorsese may have lived around the world of New York gangsters and knew it well through observation, but his true passion was always escaping to the movies, so in an unexpected way Hugo feels almost autobiographical. I never would have imagined that “whimsy” was in Scorsese’s filmmaking vocabulary, but he proves to be full of it here. Who the film will appeal to is a reasonable question, given that children don’t necessarily pine for an homage to George Méliès and most adults probably won’t want to sit down for a whimsical childhood adventure. The film will definitely be a tough sell, but should be seen and appreciated by anyone with a childlike love of movie magic. More than anything else, Hugo is a master filmmaker’s ode to the enduring escapist power of the movies and offers a rich and rewarding experience to get lost in at the cinema. It will never be in the running for the best film of Marty’s career, but very well could be the best thing he’s made in a decade.