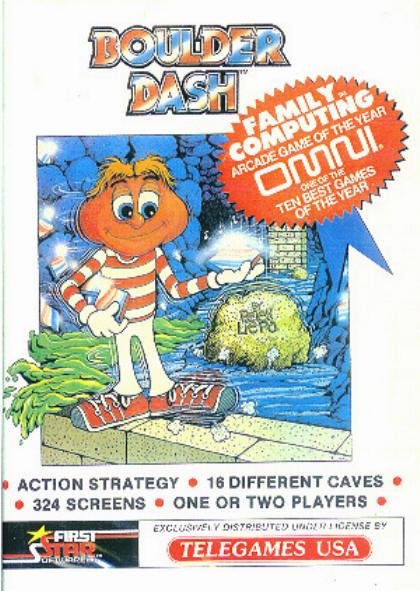

Throughout the history of gaming there have been few games that have been as enduring as or as frequently imitated as Peter Liepa’s Boulder Dash. Over its lifespan the title has been released on over fifteen different systems, reproduced in numerous flash games and cloned by multiple would-be designers. Despite a seemingly simple concept, the game brought with it an addictive edge that only a handful of great games have ever been able to capture.

Though this terse description of the game’s mechanics may leave the average gamer wondering what all the fuss is about, Boulder Dash manages to bring it all together in a rather unique and interesting way. It provides a gameplay experience that somehow superceeds its fundamental elements and draws a player in, slowly but surely. Peter Liepa, the game’s designer and programmer, has one theory on how the game managed to accomplish this.”It’s probably true that all successful games have to appeal to both our emotions and our intellects. Boulder Dash combines the action and puzzle genres. The interaction of Rockford with rocks and dirt is easy to understand, has a palpable reality, but leads to `complex yet predictable outcomes. So a player feels in control (indeed nothing happens unless Rockford moves), and knows that success is possible without fine motor control or quick reflexes.”

Though this terse description of the game’s mechanics may leave the average gamer wondering what all the fuss is about, Boulder Dash manages to bring it all together in a rather unique and interesting way. It provides a gameplay experience that somehow superceeds its fundamental elements and draws a player in, slowly but surely. Peter Liepa, the game’s designer and programmer, has one theory on how the game managed to accomplish this.”It’s probably true that all successful games have to appeal to both our emotions and our intellects. Boulder Dash combines the action and puzzle genres. The interaction of Rockford with rocks and dirt is easy to understand, has a palpable reality, but leads to `complex yet predictable outcomes. So a player feels in control (indeed nothing happens unless Rockford moves), and knows that success is possible without fine motor control or quick reflexes.”

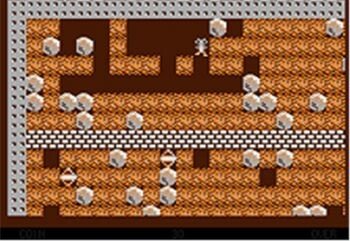

Another possible factor in the game’s incredible longevity and addictive nature could quite possibly be the random way in which the game’s levels were created. Nearly all games produced, puzzle or no, use specifically designed levels in order to provide the player with a challenge. Every aspect of the level is carefully planned and layed out. In Boulder Dash however, Liepa had a different philosphy.

“I was fond of using random generators to create as much of the caves as possible. I would then add a few walls and enemies to channel caves into specific themes. In general, I like randomness as a way to create game scenarios.”

The game’s organic nature was something integral to the project from day one. Reading over Liepa’s explanation of how the game came to be even the game’s very genesis is marked with a lack of heavy handed planning or presupposition.”A few years after finishing university I was freelancing as a software developer. A friend was into playing videogames on Atari systems, and I decided that was something I could do. So I bought an Atari 800 and asked a local publisher what kind of games were in demand. Another programmer had written a demo of a digging game. I didn’t personally think the demo was very good, but I started playing with the mechanics of rocks and dirt until I had something fun. Originally, it was just about excavating and negotiating through the rocks without getting killed or trapped. The game evolved from there.”

The game’s organic nature was something integral to the project from day one. Reading over Liepa’s explanation of how the game came to be even the game’s very genesis is marked with a lack of heavy handed planning or presupposition.”A few years after finishing university I was freelancing as a software developer. A friend was into playing videogames on Atari systems, and I decided that was something I could do. So I bought an Atari 800 and asked a local publisher what kind of games were in demand. Another programmer had written a demo of a digging game. I didn’t personally think the demo was very good, but I started playing with the mechanics of rocks and dirt until I had something fun. Originally, it was just about excavating and negotiating through the rocks without getting killed or trapped. The game evolved from there.”

Humoriously, considering the game’s Gilligen’s Island like longevity, when asked if he had any idea that the game he was working on would become such a huge success, Liepa replied, “No idea what-so-ever. I knew it was a good game, but [I] was more concerned about simply getting it published.”

But ultimately, regardless of the initial intent or expectations, Liepa has maintained a clear view of just what’s most important in gaming, remarking, “I’m happy that it connected with so many people.”