It’s very difficult to review Dear Esther using the kind of standards that would apply to the average videogame or, for that matter, even the average film or book. That’s because it doesn’t really belong to any of these forms of traditional media. It isn’t interactive enough to be a game and too much so to fit into either of the other categories.

Since the plot and the sense of exploration that goes into Dear Esther is so instrumental to the impression it makes, it also doesn’t seem possible to go forward with writing the rest of this review without putting a big fat warning up front: play the game first. Whether you think it is good, bad or even a videogame at all, Dear Esther is worth your time if you’re willing to take part in a fairly successful experiment in videogame narrative. Though it will likely make you question where the line should be drawn between interactive and passive media, exploring this title for the first time is a truly unique experience and one that’s worth entering into without any preconceptions.

So, stop now or keep going. Your call, but fair warning . . .

***

A rocky beach, a rundown wooden structure and cliff faces. Your character walks slowly as you make your way up into the cabin, reading a letter that begins with “Dear Esther . . .” There’s nothing inside the dark space so you and the character both begin walking along the beach. After a few minutes of travelling along the sand and stones your character looks down and sees a symbol drawn into the surf with a stick. The inner monologue begins again.

These first few moments of the game set the pace for the rest of Dear Esther, a title that moves extremely slowly, but always encourages forward movement. The details of the story, once the player has uncovered them, are simple, but the telling of them is the remarkable part.

At times the inner monologue prose that provides the bulk of Dear Esther’s exposition can be needlessly obtuse. Many lines of dialogue are overwritten or so vague that they discourage any sense of feeling “in place” amidst a setting that is already so mysterious. This is, ultimately, okay. The confusion that comprises much of the game becomes clear enough by the time it’s wrapped up (roughly an hour and a half after it begins) and the bewilderment that players will feel on their first playthrough is an essential part of the narrative.

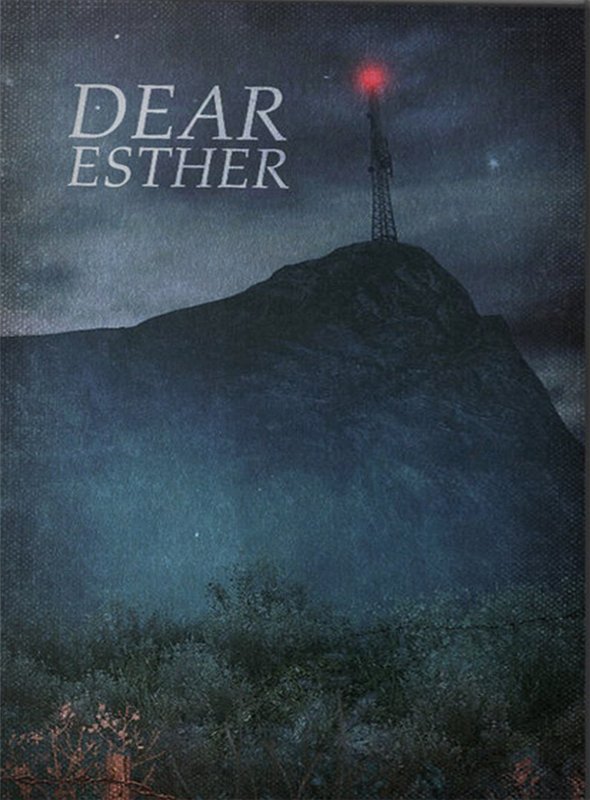

Dear Esther looks beautiful, the wonderfully realized aesthetic of a remote island in the Hebrides lending as much to the atmosphere of the game as any of the words spoken by its protagonist. Developers thechineseroom and Robert Briscoe have taken the framework of their original Half-Life 2 mod and painstakingly reconstructed their work. This attention to graphical fidelity pays off very well and helps to create the kind of wonder that makes the player want to simply stop and admire the various locations they move through during their travel across the island.

Certain moments are appropriately breathtaking. When the protagonist is making his way through a series of interconnected caverns with rushing waterfalls, phosphorescent mushrooms and dripping stalactites we, the players, are as overcome with the grandeur of the scenery as he is by the immensity of his emotional journey. Leaping into a hole in the ground toward a dark body of water far below is as much of a comment on the player’s willingness, by this point, to submit to mortal danger as it is to the protagonist’s resignation to his own death.

The environment is, ultimately, as much of the story as anything else because of moments like those. Like the games that provide Dear Esther’s graphical framework — Valve’s Half-Life series and the Source engine — the fine details players will encounter throughout their exploration of the landscape are an essential part of the narrative. Not only do story elements come through by letting players happen upon, say, a makeshift altar created around a damaged car tire — the environment also functions as a key element in the creation of Dear Esther’s grim mood. This is one of the reasons that the game suits its medium: the manner by which its audience “discovers” the plot simply wouldn’t work in the same way if it was presented as words on a page or framed shots in a film.

Despite this success, the world of Dear Esther is also strangely lifeless in other ways. The high level of environmental detail puts other elements of the game in stark contrast: walking through the landscape cause no dynamic sound to occur and the protagonist seems to drift, ghostlike over the landscape. Perhaps this is intentional, but, even if so, it’s to the detriment of what can otherwise feel like a truly organic world. While moving across rough terrain like slippery, ascending rock beds or beaches where the tide is washing over the sand, the player is forced to imagine themselves into the situation more than a videogame should require. A bit of give and take to the motion — a slight stumble here, a change in movement speed there — would go a long way toward really establishing the kind of physicality that is so notably absent.

Games like Metro 2033 and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare have demonstrated extremely effective ways to add this level of engagement from a first-person perspective. A reaching hand, obscured field of view or jerky, hobbling navigation accompanied by suitable audio cues — each of these techniques work to ground the action and force the player further into the skin of the character whose eyes they’re supposedly looking out from. Though Dear Esther manages to accomplish some of this in a different manner, it would be an even more remarkable game if it went a step further by taking cues from titles like those mentioned above.

The melancholy soundtrack helps to compensate for this presentational shortcoming. Comprised primarily of plaintive violins and pianos, the score is wonderfully constructed and has been implemented to game progression in a way that makes it feel completely natural and wholly essential. Like a good film, it’s impossible to imagine Dear Esther’s most poignant scenes possessing the same level of emotional gravity without the subtle introduction and removal of its excellent music.

Aside from this type of comparison, though, it’s important to note just how little the rest of Dear Esther’s construction borrows from other, better established media. It is, in the end, very much a videogame. Even though it’s a strange videogame, unlike almost any other title currently released, it remains a part of the format that shows just how far clever developers can stretch the definition of a game. For this reason, and for the fact that it delivers on its promise as a bold experiment in interactive narrative, Dear Esther comes highly recommended to any players interested in unorthodox — and compelling — game design.