I’m aware I start a lot of reviews this way, but say it with me: I really didn’t know what to expect with Dustborn. It might seem hacky to consistently start reviews that way, but I think that’s the double-edged sword of the indie scene that both excites and infuriates me. Developers take big risks, and when you swing big, you either hit big or miss big.

However, Dustborn is exactly the kind of game I really hate writing a review about. If you’re familiar with my writing, you’ll know there’s a certain degree of excitement in writing either a really positive or really negative review. But Dustborn is one of those games that neither thrills nor aggravates me enough to incite a real response, and it’s a shame.

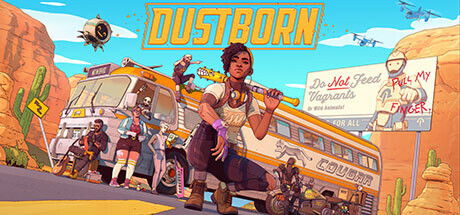

Dustborn stars a ragtag group of superpowered misfits on a mad dash to Canada, led in part by the player character Pax. After a daring heist to steal some information from the extremist group known as “The Puritans,” Pax and her three friends must travel across the equally extremist United States known as “The Republic” in order to get to the safety of Nova Scotia—where the recipient of the data is waiting.

Going undercover as a rock band touring the Republic, Pax and her friends try to outwit the authorities, get into fights with gangs and even make some new friends along the way. While it’s not a terrible story it feels both overly simplistic, while piling so many themes on top of each other that they kind of get lost amidst themselves.

Dustborn’s plot has elements of alternate history fiction so they could’ve gone in really bold directions. Instead, it has a group of religious extremists, literally called The Puritans in case you missed the point, hunting down anyone with superpowers—they prefer to be called Anomals—seemingly because anyone that is different is evil.

At the same time, The Puritans seem to have a fragile peace with The Republic since they’re forbidden from operating within Republic-controlled states, but The Republic is seemingly just as extremely authoritarian as The Puritans. So it’s like you have an extreme religious allegory ON TOP of an extreme political allegory, but they’re both aimed at the far-right, so they don’t really contrast each other in a meaningful way.

And it all just feels so painful on the nose. Pax and her friend’s powers are essentially supercharging words in order to affect people around them and they call these powers Vox. This, of course, is a reference to “Vox Populi, Vox Dei,” or “The voice of the people is the voice of God.” So our rebellious heroes are fighting against the authoritarian regime with a power that’s literally a reference to a political pamphlet about human equality…you know what, I take it back; this game might be too subtle.

“Dustborn shakes things up in a few ways that set it apart from the standard Telltale fare…”

Also, as a Canadian, I couldn’t help but laugh at the idea of Canada as this idyllic bastion of freedom from oppressive right-wing regimes. To the point on the in-game map, they made a point to write “Socialists” on Canada like that’s where they are. Guys, we’re basically Diet USA, in any right-wing extremist interpretation we’re gonna be right there with you.

Anyway, it was the gameplay that really surprised me in Dustborn. Not because it’s particularly remarkable, but just because I wasn’t expecting everything it was doing. At its core, Dustborn is a Telltale style “choose-your-own-adventure” narrative game where players engage in conversations, and crucial decisions will affect how the story progresses and how characters interact with you.

It’s been six years since I had played one of these—having been thoroughly exhausted by them in the lead-up to Telltale’s closure—so enough time has passed that I was genuinely interested in it again. But Dustborn shakes things up in a few ways that set it apart from the standard Telltale fare, and while it’s got some good ideas, it’s the presentation that keeps it from being something truly remarkable.

“It ends up feeling like a ‘too many cooks’ situation. Dustborn tries to have a lot of content…but fails to focus on one enough, so it truly stands out.”

Credit where it’s due; I do genuinely like the idea of giving players a brief glimpse into how a conversation choice might go. It doesn’t outright tell you what’s going to happen, but it gives you enough of an idea to help guide your decisions. I also like that since Vox is a vocal ability in Dustborn, there are ways to use it in dialogue to different effects.

However, my issue with the dialogue scenes, much like with The Walking Dead games, is that every conversation feels so forced. These games, despite how much is centred around people talking, have never EVER found a way to make dialogue feel naturalistic, so instead of four people having a conversation, you have four people just reading lines.

What’s more, even though Dustborn allows players to preview what a choice could be, they still have to have characters chime in on the fact that you’re not responding, which kind of makes sense diegetically but fails to account for the player trying to read what the choice might yield.

“I also like that since Vox is a vocal ability in Dustborn, there are ways to use it in dialogue to different effects.”

Every time I was trying to see my options, only for characters to repeatedly ask, “Are you going to answer me?” I found myself yelling at the screen, “Can I think for five seconds?” However, I will say that I do like that, in certain situations, if players don’t make a dialogue decision within a certain amount of time, they start to get taken away and replaced with other options, which does feel a lot more realistic in how conversations can escalate or deescalate.

Outside of combat, players will also partake in a whole host of whacky misadventures. Much like the Telltale games, there is a vast collection of situational “mini-games” players will participate in but chiefly among them are combat and Guitar Hero.

Combat in Dustborn takes a much more active approach than these games usually do, actually leaning more towards feeling like a proper action game than a more fleshed-out QTE. And while there’s a unique idea in Pax using her Vox or working together with her teammates, the combat is so stilted and fairly rudimentary that it never does anything more than feel like a mindless button masher.

“Dustborn feels like a comic come to life, and it really enhances the cel-shaded aesthetic.”

And since Pax and her friends are undercover as a Punk Rock band, they occasionally need to practice songs and play gigs to keep up the facade. Again, this is a fairly standard rhythm game that actually apes Guitar Hero more than it really innovates and ends up being pretty generic. There is a unique tension that performing badly can actually affect the plot and cause things to go south, but since the actual rhythm game is so simple, I never had to worry.

It ends up feeling like a “too many cooks” situation. Dustborn tries to have a lot of content—to quote its Steam page, “gameplay as varied as its landscape,” which is certainly admirable—but fails to focus on one enough so it truly stands out.

However, where Dustborn really shines is in its visuals. The whole game—from the pallet to the presentation—has an incredible comic book style that utilizes the form of comics to enhance the visual storytelling. From the way thoughts or environmental details are placed in square boxes, to the way instructions or SFX words are placed in physical space, Dustborn feels like a comic come to life and it really enhances the cel-shaded aesthetic.

However, the audio is slightly less impressive. While each actor does an excellent job bringing their character to life—excluding the aforementioned stilted dialogue—and the music is mostly good, there are a few balancing issues, mostly noticeable when using a Shout in combat that has no reverb or EQing, so it just sounds like Pax is speaking normally. I couldn’t help but laugh the first time I heard it, thinking to myself, “Well, it’s not exactly a Fus Ro Dah, is it?”

I honestly don’t think Dustborn is a bad game. It’s just not a remarkable game, and as I’ve said before, sometimes that’s worse. Every time it got close to being good, the story or the gameplay would pull me away from it. I think there’s definitely a lot for players to like, but if you played these kinds of games in the past, it really doesn’t do enough to elevate.