Some of the most impressive horror films of the last 20 years have not been the result of big budgets. Massive blockbusters (and two movies that, embarrassing or not, I found extremely chilling when I first saw them) like The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity were both made by passionate and thrifty filmmakers who understood that no amount of lavish special effects can ever achieve the level of terror that the human mind creates on its own with just a little bit of prompting.

Jasper Byrne’s Lone Survivor, a game made by one designer without the benefit of publisher funding, understands this, too.

Like the best entries in the Silent Hill series, Lone Survivor knows that the most frightening experiences take place in our heads and, much like the game’s title suggests, become exponentially worse when we’re left alone without anyone to help us distract ourselves from our thoughts. The story involves a young man, dressed in button-down shirt, tie and surgical mask, trying to eke out some type of life from within the confines of his apocalypse ravaged apartment building. His only real refuge is his rooms — a kitchen, bathroom, bedroom and living area — and the supplies he has managed to accumulate there. Knowing that he can’t survive forever with what he has on hand, our protagonist begins to venture out into the rest of the building, looking for an exit from the devastated apartments while avoiding the creepy mutants roaming the halls and attempting to gather enough food, weaponry and tools to keep himself afloat.

Lone Survivor is, basically, an adventure game. Players progress slowly, moving through the ruined buildings room by room, often with the help of keys and items that solve gruesome little puzzles (in one instance early on, finding a pair of scissors allows the main character to cut his way through a fleshy obstruction blocking his way into a hole in a wall). Traversal is aided by finding maps, flashlight batteries, a gun (with sparse ammunition) and the food necessary for warding off crippling hunger pangs.

While there are occasional moments of action, players having to weigh the pros and cons of attempting to gun down predatory mutants against sneaking through the darkness, tossing out flares or distracting enemies with chunks of rotting meat (lovely), the real core of the experience is less focused on gunplay than it is on basic survival. Byrne elevates an already constantly oppressive atmosphere by implementing systems that require the player to regularly get sleep when tired (which also saves the game) and eat food. This element adds to the tension of an experience built on scarcity, heightening the sense that, yes, death is looming around every corner.

Once, after going without the flashlight for what felt like forever, I stupidly broke from my hiding place to try to snatch up the batteries I had been looking for for so long. This impulsiveness put me right in the way of a mutant and, moments later, I was restarting from the last save point (losing roughly half an hour of progress). Moments like these, where the game’s mechanics make the player feel just as cagey and desperate as the character they’re controlling, capture the essence of the survival horror genre in a way that hasn’t been approximated in a very long time.

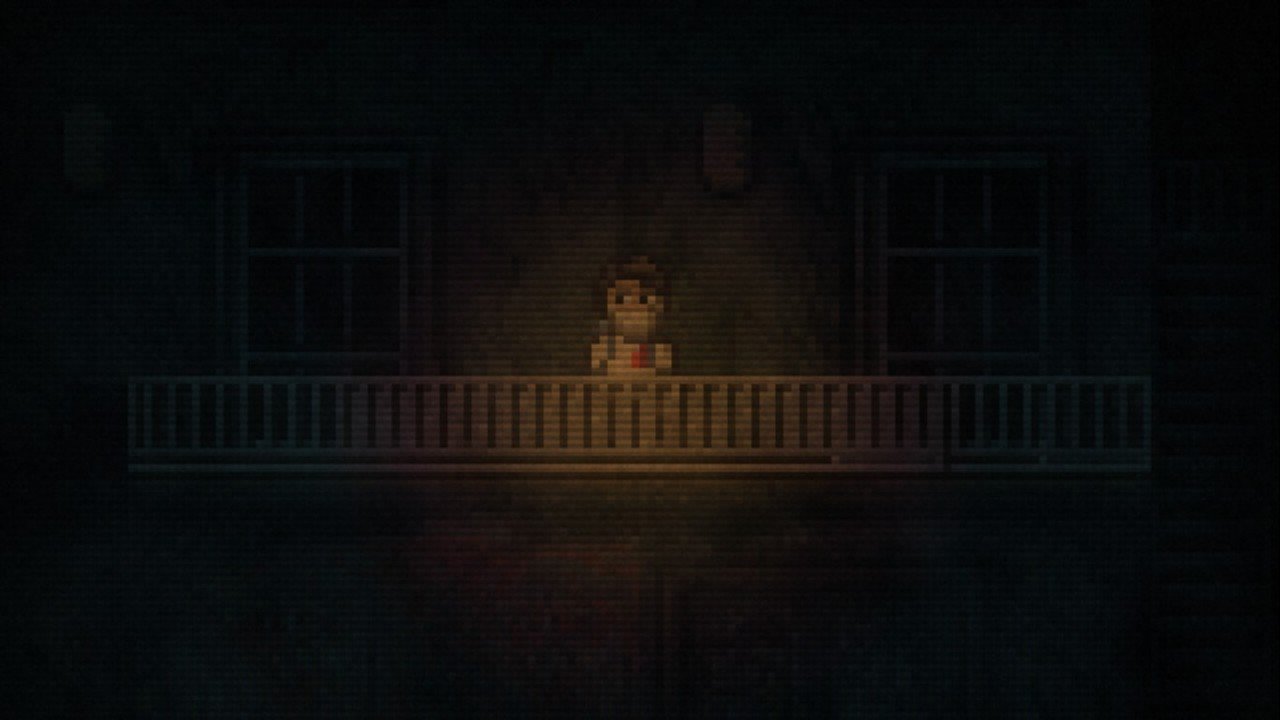

Lone Survivor’s 16-bit, 2D aesthetic may not, at first blush, look like it would help enhance the sense of despair that the game’s plot and mechanics introduce, but, after spending a handful of minutes in Byrne’s world, the graphical choice seems appropriate. The simplicity of the art style lends itself well to a setting where terror is as often implied by subtle cues (shifts in music and sound effects or the presence of post-processing layers of static and film tearing) as it is displayed outright (by the appearance of nasty monsters). Where a game built with stunning three dimensional models might risk showing too much of its threats, making them appear too real and, ultimately, fallible, Lone Survivor’s shambling, roughly defined horrors give players the ability to more freely interpret what they’re seeing — and posit a kind of grotesquery that more rigid designs would lose.

Lone Survivor also furthers its unsettling tone with a great soundtrack that obviously draws heavy inspiration from Akira Yamaoka’s superb Silent Hill scores. The music contains as many hints as to what is going on as any of the visuals or written text and succeeds immensely in informing the mood of a given gameplay moment. Atonal guitars, pianos and grinding metal accompany the most outright unnerving moments, ambient creaks and breathing make exploration truly eerie and times when spontaneous 12 bar blues or upbeat pop rock fill the player’s headphones (also: wear headphones while playing) grant as much relief as any brightly lit room or ammunition stash.

The pixel art is shown in a noticeably large format, the game’s field of view full of blown-up sprites that, by never pulling back quite far enough to lend a sense of removal, create a claustrophobic atmosphere where the player is always face-to-face with whatever gruesome environment or enemy the game cares to show. While this choice works extremely well during traversal, the effect isn’t as welcome when applied to the game’s frequent dialogue boxes. Lone Survivor is full of internal monologues and conversational text (between whom I won’t mention — this is a game that is a lot of fun to experience without too much prior plot knowledge) that is conveyed via big, headache-inducing characters.

The dialogue isn’t incredibly elegant either, but it is successful in communicating the mood Byrne is going for. The survivor’s thoughts are suitably paranoid, alternating between stating basic facts about the situation to less grounded behaviour like, well, talking to stuffed animals. Clumsy or not, the writing is extremely successful in making the player second-guess just about all information provided. While almost every scrap of text contains useful clues that help to paint a clearer picture of just what exactly is going on, there is an almost equal amount of mystery that makes a plot focused on questions of reality, sanity and medication as addled as it should be.

Resident Evil is an action series now and Silent Hill has pretty much completely lost its way in recent years, leaving the tradition of survival horror pretty well done for. Jasper Byrne is carrying the torch, though, getting to the heart of the very best entries to the genre and putting his own unique spin on its conventions. Those interested in a frightening and thoughtfully designed gameplay experience owe it to themselves to look into Lone Survivor.

ult of big budgets. Massive blockbusters (and two movies that, embarrassing or not, I found extremely chilling when I first saw them) like The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity were both made by passionate and thrifty filmmakers who understood that no amount of lavish special effects can ever achieve the level of terror that the human mind creates on its own with just a little bit of prompting.

Jasper Byrne’s Lone Survivor, a game made by one designer without the benefit of publisher funding, understands this, too.

Like the best entries in the Silent Hill series, Lone Survivor knows that the most frightening experiences take place in our heads and, much like the game’s title suggests, become exponentially worse when we’re left alone without anyone to help us distract ourselves from our thoughts. The story involves a young man, dressed in button-down shirt, tie and surgical mask, trying to eke out some type of life from within the confines of his apocalypse ravaged apartment building. His only real refuge is his rooms — a kitchen, bathroom, bedroom and living area — and the supplies he has managed to accumulate there. Knowing that he can’t survive forever with what he has on hand, our protagonist begins to venture out into the rest of the building, looking for an exit from the devastated apartments while avoiding the creepy mutants roaming the halls and attempting to gather enough food, weaponry and tools to keep himself afloat.

Lone Survivor is, basically, an adventure game. Players progress slowly, moving through the ruined buildings room by room, often with the help of keys and items that solve gruesome little puzzles (in one instance early on, finding a pair of scissors allows the main character to cut his way through a fleshy obstruction blocking his way into a hole in a wall). Traversal is aided by finding maps, flashlight batteries, a gun (with sparse ammunition) and the food necessary for warding off crippling hunger pangs.

While there are occasional moments of action, players having to weigh the pros and cons of attempting to gun down predatory mutants against sneaking through the darkness, tossing out flares or distracting enemies with chunks of rotting meat (lovely), the real core of the experience is less focused on gunplay than it is on basic survival. Byrne elevates an already constantly oppressive atmosphere by implementing systems that require the player to regularly get sleep when tired (which also saves the game) and eat food. This element adds to the tension of an experience built on scarcity, heightening the sense that, yes, death is looming around every corner.

Once, after going without the flashlight for what felt like forever, I stupidly broke from my hiding place to try to snatch up the batteries I had been looking for for so long. This impulsiveness put me right in the way of a mutant and, moments later, I was restarting from the last save point (losing roughly half an hour of progress). Moments like these, where the game’s mechanics make the player feel just as cagey and desperate as the character they’re controlling, capture the essence of the survival horror genre in a way that hasn’t been approximated in a very long time.

Lone Survivor’s 16-bit, 2D aesthetic may not, at first blush, look like it would help enhance the sense of despair that the game’s plot and mechanics introduce, but, after spending a handful of minutes in Byrne’s world, the graphical choice seems appropriate. The simplicity of the art style lends itself well to a setting where terror is as often implied by subtle cues (shifts in music and sound effects or the presence of post-processing layers of static and film tearing) as it is displayed outright (by the appearance of nasty monsters). Where a game built with stunning three dimensional models might risk showing too much of its threats, making them appear too real and, ultimately, fallible, Lone Survivor’s shambling, roughly defined horrors give players the ability to more freely interpret what they’re seeing — and posit a kind of grotesquery that more rigid designs would lose.

Lone Survivor also furthers its unsettling tone with a great soundtrack that obviously draws heavy inspiration from Akira Yamaoka’s superb Silent Hill scores. The music contains as many hints as to what is going on as any of the visuals or written text and succeeds immensely in informing the mood of a given gameplay moment. Atonal guitars, pianos and grinding metal accompany the most outright unnerving moments, ambient creaks and breathing make exploration truly eerie and times when spontaneous 12 bar blues or upbeat pop rock fill the player’s headphones (also: wear headphones while playing) grant as much relief as any brightly lit room or ammunition stash.

The pixel art is shown in a noticeably large format, the game’s field of view full of blown-up sprites that, by never pulling back quite far enough to lend a sense of removal, create a claustrophobic atmosphere where the player is always face-to-face with whatever gruesome environment or enemy the game cares to show. While this choice works extremely well during traversal, the effect isn’t as welcome when applied to the game’s frequent dialogue boxes. Lone Survivor is full of internal monologues and conversational text (between whom I won’t mention — this is a game that is a lot of fun to experience without too much prior plot knowledge) that is conveyed via big, headache-inducing characters.

The dialogue isn’t incredibly elegant either, but it is successful in communicating the mood Byrne is going for. The survivor’s thoughts are suitably paranoid, alternating between stating basic facts about the situation to less grounded behaviour like, well, talking to stuffed animals. Clumsy or not, the writing is extremely successful in making the player second-guess just about all information provided. While almost every scrap of text contains useful clues that help to paint a clearer picture of just what exactly is going on, there is an almost equal amount of mystery that makes a plot focused on questions of reality, sanity and medication as addled as it should be.

Resident Evil is an action series now and Silent Hill has pretty much completely lost its way in recent years, leaving the tradition of survival horror pretty well done for. Jasper Byrne is carrying the torch, though, getting to the heart of the very best entries to the genre and putting his own unique spin on its conventions. Those interested in a frightening and thoughtfully designed gameplay experience owe it to themselves to look into Lone Survivor.