Sitting through the screening at TIFF 2025, I was struck by the beauty and concept of Ballad of a Small Player, a mesmerizing yet flawed character study. The film showcases Edward Berger’s masterful visual storytelling and unique sense of style, yet it struggles to fully capture the essence of its troubled protagonist. The Oscar-winning director behind All Quiet on the Western Front delivers a work that dazzles with neon-soaked cinematography but occasionally loses its emotional centre amid the glittering chaos of Macau’s casino world, compounded by some slightly odd narrative choices.

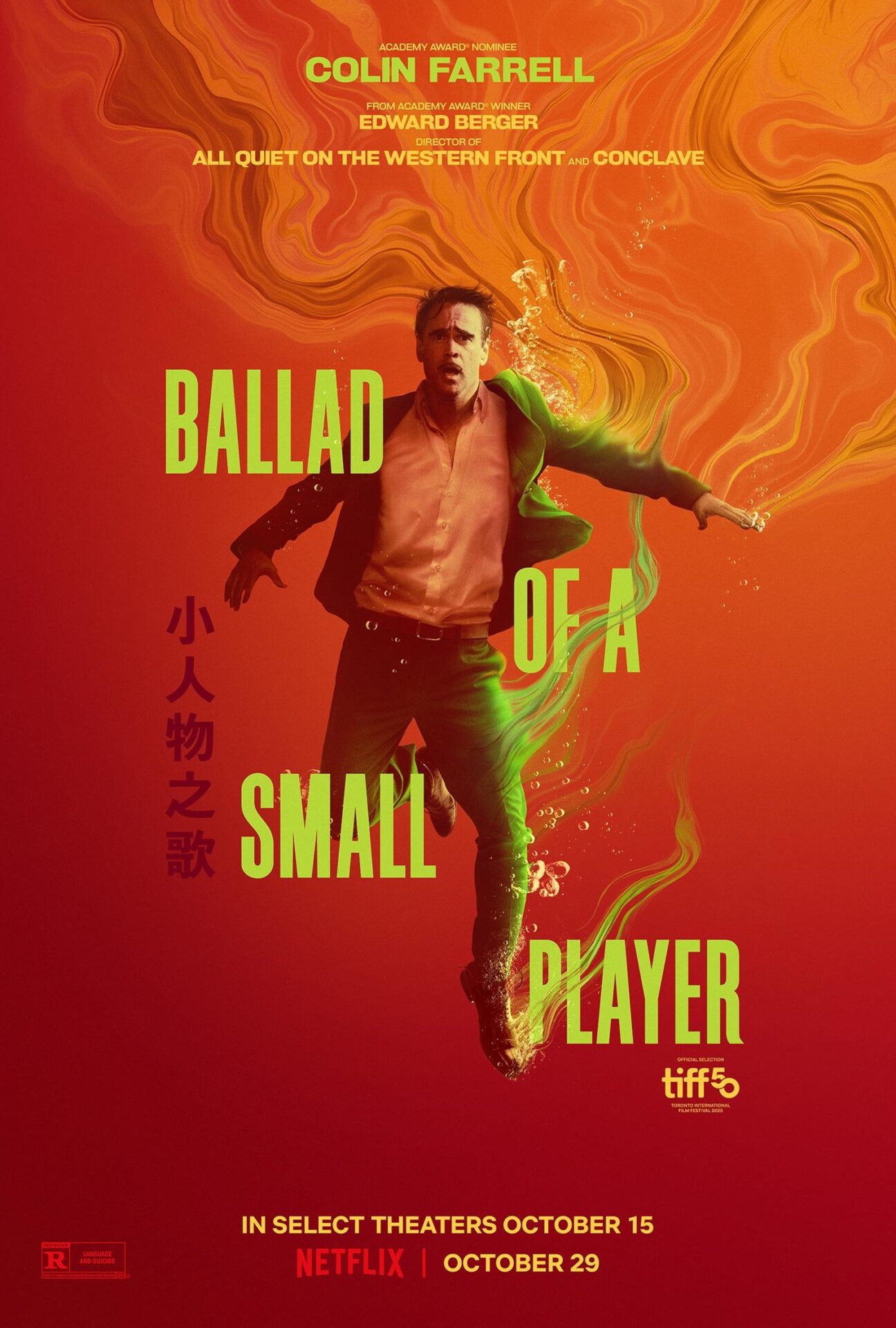

Colin Farrell fully immerses himself in the role of Lord Freddy Doyle, a desperate gambler masquerading as an international high roller in the bustling Special Administrative Region of China. Sporting a green velvet suit, pencil moustache and posh British accent, Doyle projects the façade of wealth while drowning in mounting debts and desperation. Farrell’s performance grounds the film, offering a compelling portrayal of a man whose carefully constructed identity slowly crumbles under the weight of his addictions and past mistakes. The character is at times odious but, more often than not, relatable: a man pushed to his limit by a series of bad choices.

If you go into Ballad of a Small Player expecting a grounded film like many of Edward Berger’s past offerings, you may be in for a surprise. This work weaves through the streets of Macau, blending the real with the dream and giving an almost surreal take on the subject matter. There are plenty of moments where you may question what you are seeing, unsure whether the film is toying with reality or if Farrell’s Doyle has simply lost himself in this city of money and opulence.

Berger reunites with his Oscar-winning cinematographer James Friend to craft visually striking sequences that capture Macau in vivid colours and textures, making the city itself a character in this tale of redemption and self-destruction. The neon-lit casino floors and luxury hotel corridors serve as both playground and prison for Doyle’s increasingly desperate attempts at reinvention.

“Ballad of a Small Player delivers an ambitious character study that showcases exceptional craftsmanship…”

The story grows even more disorienting once Doyle meets Dao Ming, played with nuance by Fala Chen. Their encounter pushes him further over the edge, with all sense of reality slipping away as both Doyle and the casino world lose their grip on stability. As a mysterious hostess, Dao Ming offers Doyle what seems like salvation: a chance to escape the mountain of debt weighing him down like a noose around his neck.

Chen brings depth to a role that could have easily slipped into the “mysterious woman” trope, instead creating a character with her own secrets and motivations. Her chemistry with Farrell fuels some of the film’s most compelling moments, as their relationship develops against the backdrop of Macau’s intoxicating atmosphere.

If you thought things could not get stranger for Lord Doyle, don’t worry — the film is not done yet. The story introduces Tilda Swinton’s Cynthia Blithe, who delivers a refreshingly odd performance and serves as the relentless force pursuing Doyle, even if her role feels somewhat underutilized given Swinton’s considerable talents. As the private investigator determined to confront Doyle with his past, Swinton brings her characteristic intensity, but the character’s limited screen time prevents her from making the impact the role demands. What time she does have on screen is used well, however, driving much of the film’s action and underscoring just how close Doyle is to collapse.

Even with some gripes about the story, I have only praise for the film’s visual design. The production team creates an immersive world where pop culture meets opera, drama collides with absurdity, and sincerity battles humour in every frame. Volker Bertelmann’s score complements the visual excess with compositions that heighten the film’s emotional undertones without overwhelming the character development. The supporting cast, including Deanie Ip and Alex Jennings, provides a steady foundation for the central performances.

There is much to admire in Ballad of a Small Player, but that does not stop it from stumbling in its effort to bring the story to life. Its pacing and tonal inconsistencies make it harder to connect with this world, and while its lack of grounding works at times, it fails to land the tone it aims for in the final act. The film’s 101-minute runtime can feel both rushed and meandering, as Berger tries to balance psychological thriller elements with deeper character exploration. Some sequences lean so heavily on style that visual flair overshadows emotional resonance. Still, Farrell’s committed performance consistently pulls the narrative back to its human core, even if that centre occasionally feels uncertain.

Despite these issues, Ballad of a Small Player delivers an ambitious character study that showcases exceptional craftsmanship while grappling with weighty themes of modern alienation and the search for redemption. Though it does not reach the emotional heights of Berger’s previous work, and the final act feels as if it belongs to a different genre entirely, the film offers enough visual splendour and psychological complexity to justify its place. Farrell’s layered performance alone makes this journey through Macau’s neon-lit labyrinth worthwhile, even when the destination proves frustratingly elusive.