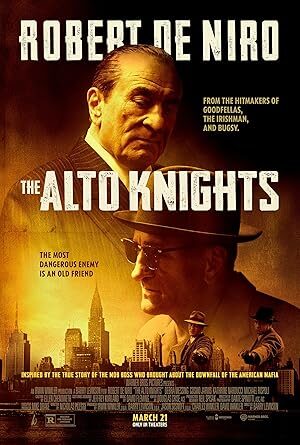

On paper, The Alto Knights seems like an easy lay-up: a crime epic about the downfall of the American Mafia written by Goodfellas scribe Nicholas Pileggi (who wrote the original novel Wiseguy, the basis for the film), directed by Bugsy filmmaker Barry Levinson, and starring Robert De Niro, whose legacy in the mob-movie genre cannot be overstated. The end result, however, is a lacklustre drama that is far less than the sum of its parts.

In the film, De Niro plays both legendary mobsters Frank Costello and Vito Genovese. Growing up together as childhood best friends during the Prohibition era, Frank and Vito eventually rise through the ranks of New York’s criminal underworld, becoming major players in the Luciano family. An extended departure to Italy by Vito leads to Frank managing the Mafia’s various rackets, his low-key demeanour and friendly connections with cops, crooks and politicians earning him the nickname “The Prime Minister of the Underworld.”

When Vito returns to America, he wants back into the family and a bigger piece of the pie, but his volatile behaviour and willingness to enter the drug trade—something Frank opposes—drives a wedge between them, kicking off a tense rivalry throughout the late ’50s. This culminates in an assassination attempt on Frank by Vito’s underling Vincent Gigante (Cosmo Jarvis). Frank survives but is shaken enough to consider retiring for good. Of course, Vito won’t make that easy.

“As Frank, De Niro is practically sleepwalking through his scenes, while as Vito, his volatility lacks any spark.”

The Alto Knights opens with the botched hit on Frank and jumps back and forth in time, simultaneously showing the bosses’ deteriorating friendship and Frank’s attempt to get out of the game alive and clean. Levinson occasionally employs true crime-style flourishes in the otherwise traditional narrative, frequently using archival footage and photography alongside Frank’s narration and occasional appearances as a “talking head” years after the film’s events.

The problem is that these flourishes feel like distractions to hide the flat writing and direction. At one point, during a scene with Vito and his crew watching Frank’s Senate hearing, the camera suddenly does a crash zoom on one of Vito’s underlings in the middle of a random line for no particular reason. It felt like a shot added by mistake, resulting in my friend and I exchanging confused glances.

None of the dialogue is particularly engaging, and I never felt the weight of this rift or that this was the end of an era. Most scenes repeat the same note: someone asks Frank to talk to Vito, Frank refuses, and things get significantly worse due to his inaction. It comes across like a petty childhood argument rather than a blood feud. Additionally, we get little insight into Frank and Vito’s friendship beyond a handful of childhood photos or seconds-long voiceovers.

There is no real sense of them as longtime friends or even occupying the same space—both figuratively and literally. They share the screen in only two scenes, and in both cases, either one is clearly overlaid against the other, or the standard over-the-shoulder shot is used when one character speaks. By the time The Alto Knights reaches its conclusion, any sense of tension has long since disappeared.

“Where The Irishman felt like a definitive closing statement on the mob-film genre, The Alto Knights feels like an unnecessary epilogue to a book that has already been closed.”

It’s amusing how between The Monkey, Mickey 17, The Alto Knights and next month’s Sinners, dual performances have become a sudden microtrend in Hollywood—especially since the latter three are all Warner Bros. films. I can’t yet judge how Michael B. Jordan fares in Sinners, but it’s surprising that, so far, Robert De Niro gives the weakest dual performance of the bunch. Both of his performances here are oddly one-note, which is especially disappointing considering his nuanced turns in The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon.

As Frank, De Niro is practically sleepwalking through his scenes, while as Vito, his volatility lacks any spark. It doesn’t help that the prosthetic chin he wears as Vito is more reminiscent of Jay Leno than anything. The supporting cast isn’t bad, but they have little to work with. Debra Messing, as Frank’s wife Bobbie, does little more than deliver concerned looks in another stereotypical “worried wife” role. Kathrine Narducci gets a livelier role as Vito’s wife Anna, but it’s just as empty.

Where The Irishman felt like a definitive closing statement on the mob-film genre, The Alto Knights feels like an unnecessary epilogue to a book that has already been closed. While it isn’t a Gotti-level disaster, I almost wish it was—at least then, I would have felt something other than apathy. Midway through the movie, there’s a scene cross-cutting Vito whacking someone while Frank watches the 1939 classic White Heat. It’s telling that I spent the rest of the film wishing I was watching that instead.