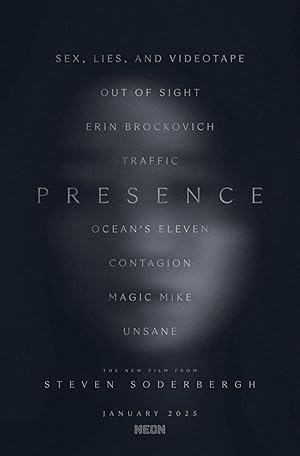

Oscar award-winning director Steven Soderbergh (Magic Mike, Ocean’s Eleven) attempted to redefine the horror genre with Presence, which premiered at TIFF 2024. The film takes an innovative approach by adopting the point of view of a housebound spirit to depict the troubled lives of a family moving into a new home. While Presence tries to push the genre forward with creative techniques, its shortcomings are hard to ignore.

After a hypnotic prologue, where the camera glides weightlessly through an unfurnished house, we meet a realtor (Julia Fox) showing the property to a married couple, Rebekah Payne (Lucy Liu) and Chris Payne (Chris Sullivan), along with their children, Tyler (Eddy Maday) and Chloe (Callina Liang). The family moves in, but their presence fails to bring warmth to the home.

Instead, a series of personal issues unfold: Rebekah faces trouble at work, Chloe is mourning a friend who recently died of an overdose, and Tyler’s friend Ryan (West Mulholland) becomes a frequent visitor, bringing questionable influence into the household. Meanwhile, the ghost silently observes and begins to intervene in eerie ways, prompting Chris to call in a spiritualist. Presence feels like a blend of influences from films such as The Conjuring, Poltergeist, Paranormal Activity, and even Scream.

For gamers, the opening prologue might evoke the movement patterns of ghosts in Phasmophobia. Interestingly, the spirit in Presence seems to have an affinity for Chloe’s closet, almost as if it’s its respawn point each time a new scene begins. The video game-like elements don’t stop there; like many supernatural depictions, the spirit wields some supernatural powers throughout the film.

“Presence feels inspired by an amalgamation of films ranging from The Conjuring, Poltergeist, Paranormal Activity to the likes of Scream.”

Ultimately, the spirit in Presence is more friendly and shy—reminiscent of a Shade from Phasmophobia. It can do things like fold your clothes when you’re too lazy, but it also breaks mirrors when it’s angry. However, the spirit’s powers seem inconsistent, as it sometimes can’t interfere with the living for plot reasons. This inconsistency raises questions—does it have a limited “mana bar” or spell slots like in Dungeons & Dragons?

Soderbergh’s cinematography and camera work in this film feels scrappy, primarily because of what the camera is meant to represent. Some shots feel like a person holding the camera and walking around like a human, while others are more spectral, almost drone-like. Though not debilitating, this inconsistency detracts from fully selling the POV as that of a spirit.

Additionally, it’s unclear where the presence goes when scenes cut away and then return. Do spirits have an on/off switch or a sleep mode? Despite these questions, I have to commend the impressive long take when the family is introduced to the house. There were opportunities for hidden cuts via wipes, but the sequence was executed smoothly without them.

Film director and screenwriter David Koepp (Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, The Mummy) wrote the screenplay for Presence, and this was one of his film stories that almost understood the assignment. The narrative was simple, though it took a turn in an unexpected direction. The parents’ storyline did not feel fleshed out enough; it was just there to add tension to the family dynamics.

By the end of the film, I wasn’t sure how to feel about Chloe’s character arc. Was I supposed to sympathize with her as an irreparably traumatized victim, or does she simply make poor decisions? Additionally, the subplot involving the parents’ alleged illegal activities remained unclear. It felt intentionally vague, possibly to heighten family tension for the sake of the plot.

In terms of character development, Chris Sullivan stood out the most as the caring, sensitive father. The film quickly established that Chris and Chloe were the more emotionally attuned members of the family, while Rebekah and Tyler took on more pragmatic roles. Lucy Liu’s portrayal of the overprotective mother was spot-on. There’s one scene in particular where Rebekah shows affection for her son in a questionable manner, to say the least.

“Film director and screenwriter David Koepp…wrote the screenplay for Presence, and this was one of his film stories that almost understood the assignment.”

The most believable and heartwarming scenes were always between Chris and Chloe. Sullivan and Liang had really good chemistry as a father-daughter relationship on-screen. Their emotions poured out a lot. I felt like Sullivan maintained his dramatic chops from the This Is Us series.

Liu and Maday played their parts well, embodying the more antagonistic side of the family when it came to the supernatural occurrences. Tyler’s dialogue, however, felt a bit overdone, with excessive F-bombs thrown in for comedic effect. Despite this, the humour worked, largely thanks to Sullivan’s impeccable line delivery, which helped sell Tyler’s sporadic cursing.

As for the sound design and score, the sound design was a peculiar choice for when the presence was not able to interact with physical objects. It sounded like it was hitting a bubble shield in a video game. The score was almost non-existent. The theme of the spirit chimed in and as mystical as music in an average medieval fantasy game like Potion Craft: Alchemist Simulator and Skyrim—less medieval but adjacent to it.

Presence was a tricky beast. It had a cool premise but lacked much conflict in the first half of the film. The story gradually evolved into a mystery, as Chloe suspected the spectre in the house might be her deceased friend who had allegedly overdosed. The Payne family’s dialogue was solid overall, though it occasionally felt cringey when focused solely on the teens. While mixing horror and thriller genres can work, this film narrowly missed its mark.

Check out more of CGMagazine’s TIFF 2024 coverage here throughout the festival.