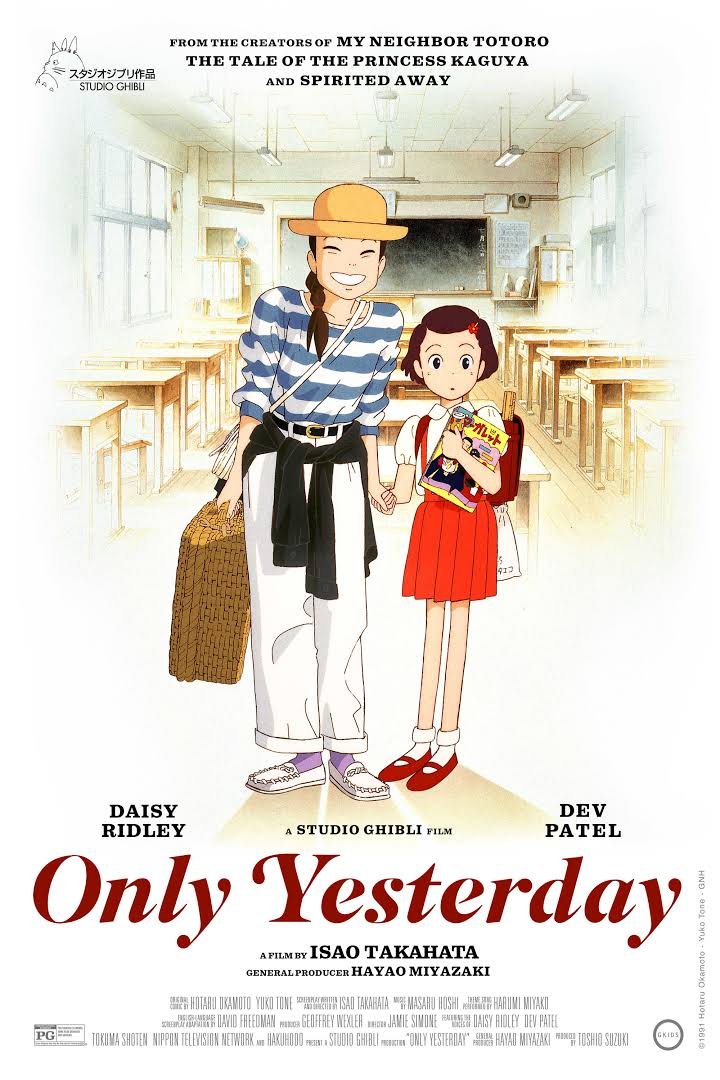

In the West, Studio Ghibli is primarily known for its whimsical fantasy films, and for good reason – that’s a majority of its output. From the moving ghost story of Spirited Away to the high-flying fairy tale of Castle in the Sky, Ghibli’s oeuvre consists primarily of fast, fluid, and fantastical fairy tales for the whole family. That said, the studio has also put out understated, slice-of-life stories that are equally captivating, albeit a bit more adult. These films usually come from the mind of Hayao Miyazaki’s lifelong friend, Isao Takahata.

Only Yesterday is Takahata’s second film for Ghibli, the first being the heartrending WWII story Grave of the Fireflies. And much like his debut, his second offering is concerned with the intricacies of human emotion when faced with conflict. Only here, the conflict isn’t centered on something as horrific as the toll of nuclear warfare on Japan. Instead, viewers get to witness one woman’s struggle to overcome her joyless, mundane existence.

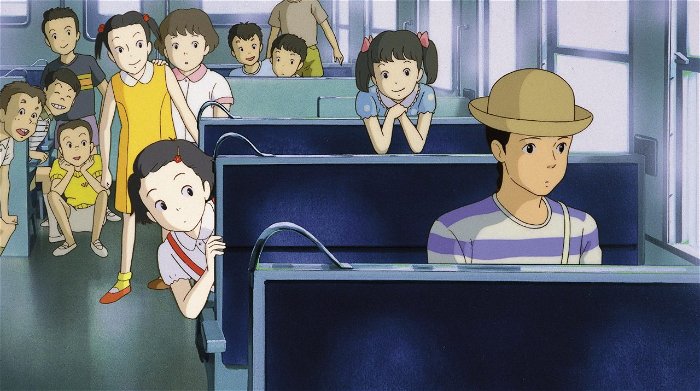

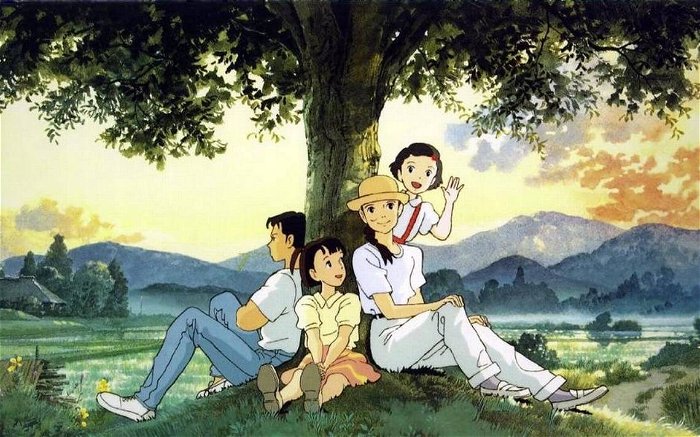

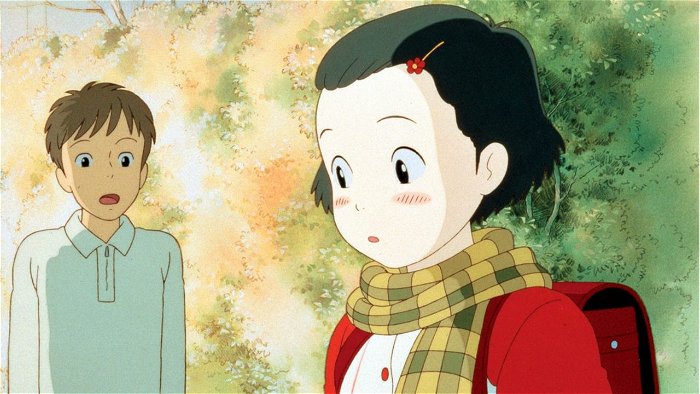

The film takes place from the perspective of two characters – twenty-seven year old Taeko Okajima and eleven year old Taeko Okajima. Yes, both are the same person, but it becomes apparent each is her own distinct character. The older Taeko is a Japanese “office lady,” a modest woman who is quietly dissatisfied with the emptiness of her life. By contrast, the younger Taeko is an enthusiastic and emotional young girl, filled with dreams of romance and fame. While there’s an initial dissonance between the two versions of her, over the course of two hours viewers start to see how the younger Saeko aged into the older one. More importantly, Only Yesterday demonstrates how a ten-day trip to the countryside helps Saeko get back in touch with her younger self, which in turn allows her to start becoming more honest about what she wants out of life.

This may sound like a relatively trite set-up. Certainly, the potential for yet another not-quite-mid-life crisis film is there. Thankfully, Takahata’s strength as a filmmaker helps him skillfully avoid any potential narrative pitfalls, and deliver something that is authentic and heartfelt throughout. There are no cheesy “rediscovering yourself” monologues or campy, upbeat montages. Everything the audience needs to know is slowly unraveled through subtle, understated verbal exchanges and anecdotes. Taeko’s quiet anxiety about femininity, for example, is revealed through a touching yet humorous flashback to learning about the menstrual cycle. Little flourishes like these prevent Only Yesterday from falling into the trappings of something like, say, Eat Pray Love.

Part of this understated tone comes from the presentation itself. Clashing somewhat with Studio Ghibli’s aesthetical trends, Only Yesterday is a remarkably still movie. High-motion sequences are limited to relatively few scenes, such as a children’s baseball game, or dreams Taeko has as a child. Most shots are lingering, focusing on things like the subtleties of characters’ facial movements or the atmosphere of the rural backdrop. This gives the film a more distinctly Japanese feeling to it than many of Ghibli’s other productions, as deliberate pacing and lingering camerawork are hallmarks of the country’s classical cinema.

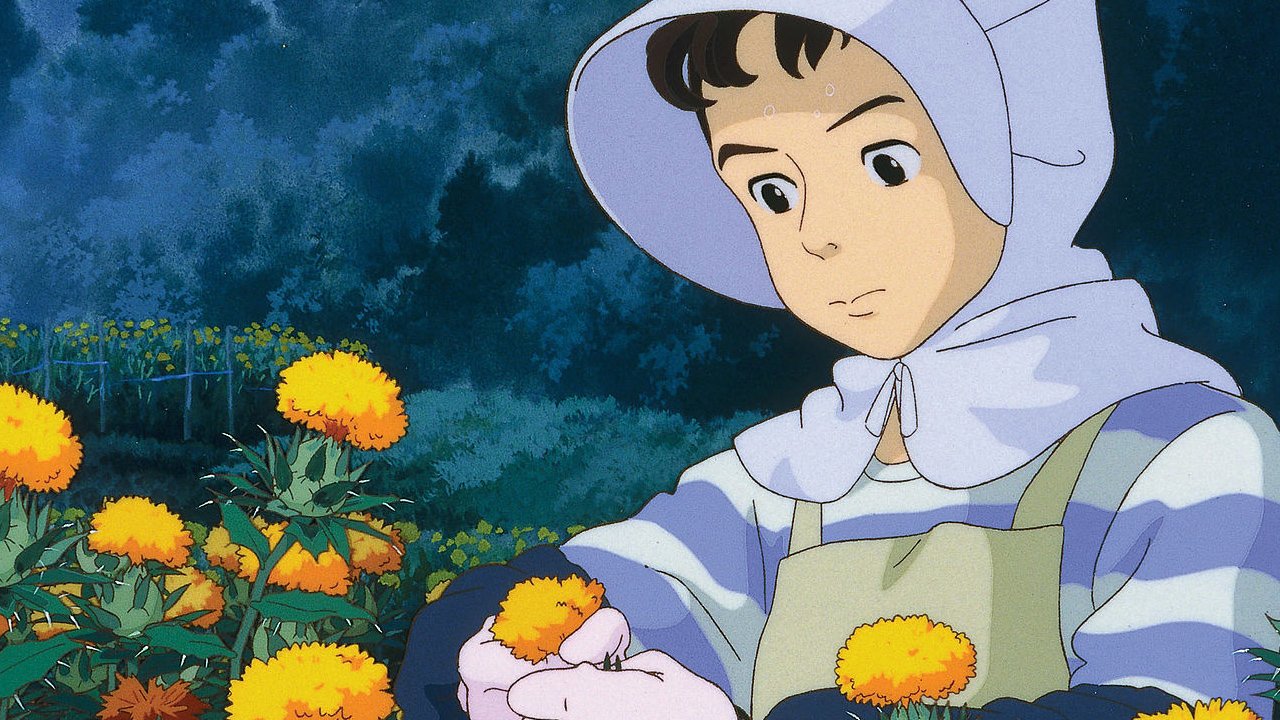

This calm stillness shouldn’t be mistaken for laziness, however. Only Yesterday is still a gorgeous film. Adult Taeko’s world is filled with vibrant primary colors and lush backdrops, while her younger counterpart’s is more defined by pastels with an emphasis on white backgrounds. Both characters, moreover, are portrayed with meticulously rendered facial expressions and character motions. Every frame of animation captures the intricacies of the human face and body in more striking detail than most CGI. It’s all so lovingly and carefully rendered that it feels practically lifelike. Even smaller details, such as trains speeding through the countryside, the moving back windows of cars in motion, and farmers grinding down saffron flowers are painstakingly recreated.

I have seen almost everything Ghibli has put out, and even some of Miyazaki and Takahata’s early creations. Few of their works, however, hold a candle to this. Only Yesterday is a masterpiece of not only animation, but of film. The nuanced way portrayal of Taeko’s identity crisis — coupled with a surprisingly mature depiction of the pressures facing women in Japanese society — feels more real and tangible than most live-action films do. It is a landmark, and the type of film that we’re lucky to see pop up once every decade or two.

Few works of art manage to put their finger to the pulse of humanity — and then replicate with such spellbinding results. Only Yesterday is one of those rare gems, and it deserves a place in any self-respecting film lover’s collection.