Penny Arcade has announced a Diversity Lounge at PAX 2014: a safe space where marginalised groups can play games and have conversations about minority issues in gaming. Within minutes of the announcement, the target community of the lounge had largely laughed this off, suggesting that it was woefully inadequate and borderline offensive.

The implication that only part of the convention would be a safe space was troubling to people who are concerned about harassment at PAX. It seems to stand in contrast to the assertion from long-time attendees that the whole convention is a pleasant, sociable place where people respect one another. The diversity lounge was understood by many as an attempt to keep difficult issues about inclusivity and change sequestered away, where the mainstream wouldn’t have to look at it. The word “ghettoisation” was used by more than one person on Twitter.

This might be hard to imagine: surely including a special space set aside for diversity will advance conversations and raise visibility — akin to the Indie Megabooth, for example? The problem is not the lounge itself, but its context at a company that has for years been dismissive and at times cruel to anyone who is not a white, straight, cisgender male. It has become hard to assume good faith from Penny Arcade after repeated incidents of disrespectful behaviour and inflammatory language toward women and minorities.

PAX is so notorious that developers such as the Fullbright Company, who made gay coming-of-age story Gone Home, have decided not to attend. Other developers are under increasing pressure to boycott the event, with LGBT-identified indies having to make a difficult choice between marketing their games and standing up for their beliefs. It’s not an easy decision for anyone. PAX is perhaps the most important place for developers to showcase games.

PAX is inseparable from Penny Arcade, which in turn is inseparable from the personalities of its two founders, Mike Krahulik and Jerry Holkins. The comic’s characters are fantasy versions of themselves that they created for fun as a hobby years ago. As the site became wildly successful, the fictional and real versions of Mike and Jerry seem to have merged together; people will describe the real-life individuals by their pseudonyms, Tycho and Gabe. When Krahulik goes on ill-informed and ill-considered rants against rape survivors and transgender people, you get the sense that he is acting both as an invincible cartoon character and a vulnerable little boy at the same time: he knows that he is powerful now, but his blogs suggest that he seems to be perpetually reliving his experience of being bullied as a child.

At the same time that Penny Arcade has been growing into a multimillion-dollar powerhouse, minority voices in gaming have become more prominent. Just as Mike and Jerry got access to a massive fanbase through the internet, the internet has been a way for unheard voices to support and amplify each other. There has emerged a social-justice-and-gaming crowd on social media, made up of fans, critics and developers alike. It is amid this process of network-building and consciousness-raising that Penny Arcade has increasingly appeared out of touch, and even wilfully offensive.

This first caught up to them when they were called out for making rape the punch line of an unfunny joke in a comic strip entitled ‘dickwolves’. Survivors of sexual abuse were upset that a comic they enjoyed was making light of their pain. What followed has become a familiar pattern: Krahulik became defensive, and doubled down with further inflammatory writing. Penny Arcade even started selling ‘Dickwolves’ T-shirts out of defiance against the criticism, which they argued was a threat to their freedom of speech.

Penny Arcade did eventually act out of concern for marginalised members of its community. They removed the merchandise from the store, explicitly stating that they were worried that survivors would feel unsafe at PAX if people were wearing the shirts. Eventually this particular issue more-or-less went away.

they don’t want to see geek culture change. They don’t want to see their heroes taken down

That is, until Krahulik bizarrely decided to bring it back up again. At PAX 2013, Krahulik was asked on stage the very open question of “what do you wish you had done differently over the past few years?” He said that he regretted pulling the Dickwolves merchandise. The crowd cheered. They cheered not necessarily because every one of them supports rape, but because they don’t want to see geek culture change. They don’t want to see their heroes taken down. As marginalised voices criticise gamer culture for the ways that it holds up rape culture, an enormous crowd of fans declares that this impinges on their freedom of speech.

Survivors of sexual abuse come away from this learning that their pain is less important than someone else’s entertainment. That is what Penny Arcade represents to many people.

Dickwolves was not the only controversy that has made PAX feel unsafe. In April of 2013 Krahulik suggested in a blog post that criticisms of Dragon Crown’s extreme objectification of women were censorship. Two months later, Penny Arcade got a lot of heat because of a panel announced for PAX Australia that seemed to be dismissive and silencing to minority concerns. “Any titillation gets called out as sexist or misogynistic[,] and involve any antagonist race other than Anglo-Saxons and you’re a racist. It’s gone too far[,] and when will it all end?”

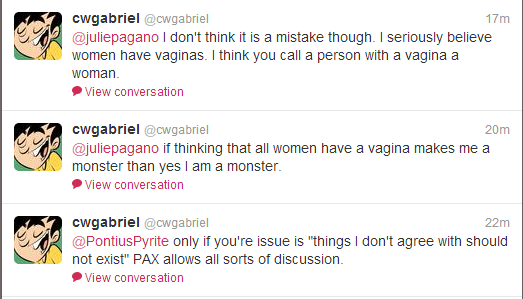

At around the same time, Krahulic was engaged in repeated rants about transgender people. “If thinking that all women have a vagina makes me a monster than yes I am a monster,” he said. An enormous argument broke out, during which he had a transgender friend vouch for him. By the end of the whole affair he had apologised and donated $20,000 to the Trevor Project.

Throughout all of this, anyone engaged in the public outcry against Krahulic’s behaviour has found themselves set upon by hard-core Penny Arcade fans. A vicious battle of words ensues; between fans who cite freedom of speech to justify their attempts to silence criticism with threatening behaviour, and social justice-oriented gamers who are tired of seeing vulnerable minorities defamed by internet celebrities.

“I’m very good at being a jerk,” Krahulic admitted in one of his apologies. “It’s sort if [sic] my superpower. When it comes to Penny Arcade it has served me well but it’s not okay when I make a bunch of people who are already marginalized feel like shit.”

Two months after writing this post, he went on stage at PAX Prime and declared that he regretted pulling the Dickwolves merchandise: failing to keep his mouth shut as promised, and once again using his “superpower” to hurt people. The crowd that cheered in response is Krahulic’s true superpower: it is not simply his ability to say cruel things, but his command of an enormous crowd of angry young men, some of whom are quite frank about their distaste for transgender people and rape survivors.

It is easy to understand that the constituents of the Diversity Lounge might be wary of stepping anywhere near that roaring crowd. It is hard to understand Krahulic’s repeated outbursts, given his stated desire to not cause any hurt and his apparent awareness of the power he has amassed through his online presence.

Back in June, Penny Arcade tried to assure people that no matter what kind of views they might espouse on the site itself and the heads’ own Twitter accounts, PAX is still safe for everyone. Jerry Holkins put out a short blog post defending PAX as a safe space for everyone:

“At root, if someone wants to know if they’re welcome at PAX, we’ve got a strong record on that front: we have panels every show that advance this very conversation, precisely because they’re submitted by attendees. We don’t define the show because we can’t. It is, in many ways, not our show.

The show is a dialogue you should be part of; the mix of people walking around

“And it’s not, like, ‘anybody can come, whatever.’ It’s like seriously, you, right there, come to the show. The show is a dialogue you should be part of; the mix of people walking around is, and has been, crucial. If somebody fucks with you, I will show you a magic trick (called “Our Harassment Policy”) where that person’s badge disappears.”

It is for this reason that many transgender and queer developers, fans and critics choose to go to PAX: they give talks, raise awareness, and try to engage the gaming community at its largest. It is already a place that people go to educate on diversity issues. If it weren’t for Krahulic’s willful ignorance and propensity toward offensive behaviour, the Diversity Lounge would probably seem like a good idea. It would simply be a way to showcase the good work that is already happening at PAX, carried out by proactive members of the community who want gaming to be more inclusive.

Against the backdrop of everything else that has gone on, however, the lounge just looks like an admission that PAX in general is not safe for marginalised people — that if a safe space is going to emerge, it will have to be separate to the main event, away from that main stage where Mike Krahulik could at any moment start another tirade against rape survivors or transgender people, to the cheers of an adoring crowd.