In January of this year, the culture of comics was hit with a surprising, saddening blow. Wizard, the magazine that has been keeping comic fans informed of the developments in their favorite medium since 1991, was going out of print. To some, this isn’t simply the phasing out of a magazine, it is a signifier of the changes that have come to a market and medium that is now probably more successful than it ever has been in its lifespan, so why would a publication that was unquestionably the #1 mainstream source for comic news flounder in a time when comics are in greater demand than ever?

We’re going to take a look back in time at a different period, a different mindset for an industry and see how the changes affected this barometer of the medium.

The Beginning

It was July of 1991 when the very first issue of Wizard hit the stands. Most people didn’t realize it then, but it was a momentous day for comics. The presence of Wizard on magazine racks and in news stand shelves made a few bold statements about comics. Wizard was an announcement that comics had grown as an industry. It was a declaration that those children who grew up reading comics had continued to read them into their teenage and even adult years. It was an admission that there were so many things happening within the industry that it was time for a professionally managed publication to step in and keep the audience informed. And it was a rallying point to that audience that they now had a “flag” to hold over their heads to represent their interests. In some ways, the debut of Wizard was a way of saying that comics, as a business, a medium and a means of artistic expression, had “arrived.”

When the magazine first went on sale in that summer of ’91, it was known as Wizard: The Guide To Comics and featured an exclusive cover of Spider-Man dressed in wizard robes, as drawn by Todd McFarlane, then one of the hottest artists in the industry. It also contained an interview with the same artist and included, previews of upcoming comics and what would become the absolute fulcrum on which the magazine would rely for years, the price guide that told collectors and speculators exactly how much their rare or collector’s issues were.

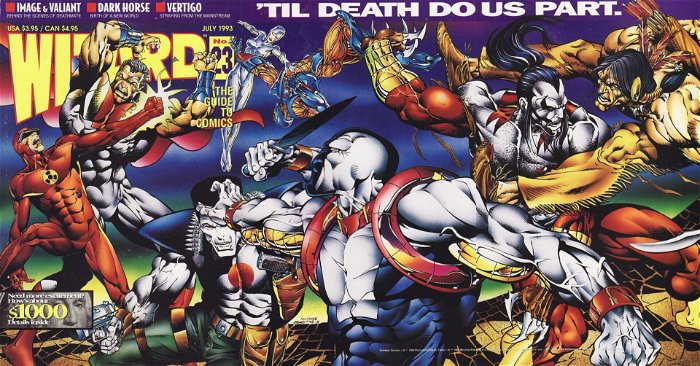

Wizard came at a very interesting time in the history of comics, because this was the last year that “the big two,” namely Marvel and DC, would ever enjoy uncontested dominance of the comic book scene (aptly named Dark Horse Comics, formed in 1986 notwithstanding) because the very next year, in 1992, Todd McFarlane who had provided the cover for their inaugural issue would form Image Comics with other luminaries from Marvel such as Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld. The timing was eerie.

Comics themselves were about to explode. Image Comics was just a taste of the rapid changes the medium would experience, with DC’s own Vertigo Imprint appearing in comic book stores just one year later in 1993. Meanwhile, the metamorphosis in more serious comic stories by writers such as Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman and Frank Miller was gaining more momentum, and the Batman movies—most notably Batman Returns in 1992—had finally proven that movies based on comic properties were a solid money maker. Wizard had the good fortune to be there for fans of the medium just as the medium itself took off with mainstream audiences.

The 90s

Wizard wasn’t actually the first publication focusing on comics, that honor goes to the Comic Buyer’s Guide, which began back in 1971. But Wizard was the first magazine to reach beyond a core audience of niche comic lovers to more casual comic fans and beyond. With content that covered the artists the characters and even playfully poked fun at the industry itself, broadening the audience of comic lovers and informing a new, younger generation that was just coming into the hobby thanks to new artists like Todd McFarlane and Jim Lee. It is also because of those artists, more specifically, their move to Image Comics and subsequent marketing tactics, that comics went through their first big “boom n’ bust period.” Because of the new found popularity of comics, the prices on old and rare issues of established titles like Batman and Spider-Man sky-rocketed, with publications like Wizard being the go-to source to find out exactly what a comic was worth, depending on its condition.

Image Comics, not having the benefit of a staple of classic heroes with a history that spanned decades, created an artificial sense of value for their comics by providing “limited” or “collector’s editions” of comics with special features like variant covers, or covers made out of foil with the deliberate intention that, as time passed, these features would increase the value of the comic. As collectors saw the value of old comics from 1930s explode in value, the promise of these Image comics seemed like an investment gold mine, and Wizard became the bible by which these comics were judged.

Unfortunately the sheer over printing of these “limited editions” and eventual collapse of the speculator market ensured that the comics would never fetch the tens of thousands of dollars in auction value that the classic comics commanded, but Wizard was there to encourage, document and ultimately analyze the fallout from this failed attempt to make comics a market commodity like fine art.

It’s also during this time that Wizard inadvertently created an army of aspiring comic book artists with features from prominent figures in the industry explaining their techniques. For people that couldn’t afford the time, tuition or mobility required to move to Dover, New Jersey and join the Kubert School of Cartoon & Graphic Art, the world of learning about comics began and ended with How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way. Wizard made it possible for hopeful artists to get new content every month about how the professionals they admired so much created the work they were trying to emulate themselves.

It was a good time for comics, and a great time for Wizard. But unfortunately, it didn’t last.

The 21st Century

With the turn of the decade, comics and Wizard began to lose some steam. Comics as a graphic novel art form was not in danger of disappearing, but the traditional superhero genre that dominated the market was losing its share. Manga from Japan began to make huge inroads, especially with a demographic that traditional comics could never reach: young women. Independent publishers like Dark Horse, Oni Press, and even Image were also eroding the food chain at the top of which the superhero sat. The comics themselves were doing well, of course, even expanding their market, but the particular comics that Wizard specialized in were no longer the undisputed rulers of the land.

But the biggest single factor that hurt Wizard and ultimately led to its demise was the same thing that hurt so many other traditional media: the Internet. The World Wide Web was just coming into its own in the 1990s, but by the 21st century it had become so ingrained in the popular culture lifestyle that the staid comic book magazine found it difficult to compete. Comic book fans have been derisively referred to as “nerds,” but that also meant that their penchant for embracing new technology and their sense of isolation from others around them made it easy for them to see the potential of websites over traditional print, and to create a sense of community among themselves thanks to online forums.

However, the biggest single factor that hurt Wizard and ultimately led to its demise was the same thing that hurt so many other traditional media; the internet. The World Wide Web was only just coming into its own in the 90s, but in the 21st century, it arc welded itself into the lifestyle of popular culture in ways that the staid, comic book magazine found difficult to compete with. Comic fans have been derisively referred to as “nerds,” but that also meant their penchant for adopting new technology and feeling a sense of isolation from others around them made it very easy for them to see the potential of websites over traditional print, and engender a sense of community amongst themselves thanks to online forums.

Where before, they could only get a taste of their hobby’s culture on a monthly basis thanks to Wizard, the rise of the internet, its forums, newsgroups and rapid proliferation of hobbyist websites—with information updated daily, sometimes even hourly—made the idea of waiting an entire month for new information outdated. Wizard lost readers as they flocked online to a more interactive world where it was faster, easier and more community oriented than the solitary activity of waiting every month for a new issue.

Wizard shrank. From a thick publication with a glossy cover and numerous features, the magazine lost content and was forced to advertise with the most unlikely of clients. From full-page, full-color ads announcing the latest maxi-series from DC or Marvel, Wizard was reduced to accepting ad space from up-and-coming bands as the magazine’s traditional advertisers realized the audience had gone online.

And now, it seems, so has Wizard. Although the print magazine is dead, it has been announced that it, along with its defunct sibling ToyFare, will return to readers in digital form. Wizard World, currently a website that updates readers on the latest activities at Wizard World conventions across the continent, will carry the banner of both Wizard and ToyFare as a digital magazine. It’s unclear at this point whether a digital version of Wizard will draw comic readers away from the established forums and websites, but at this point it’s the only outlet left for fans of the magazine. Wizard may be dead on the printed page, but there’s a chance that the spirit of the magazine can still find a voice as a digital magazine. Only time will tell.