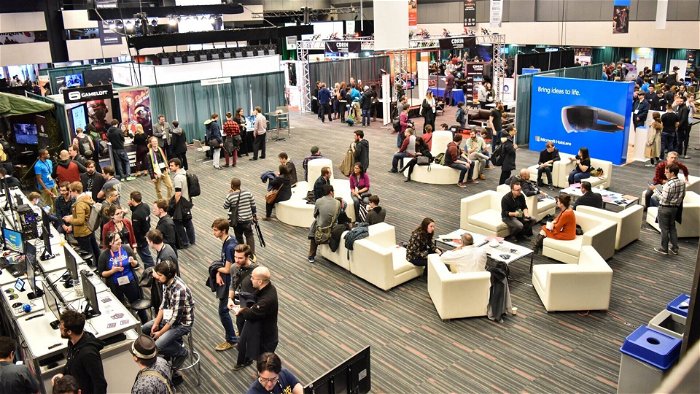

For seven years now, the Montreal International Games Summit (MIGS), organized by Alliance Numérique, has been offering high level conferences presented by renowned experts in business, arts and visual effects, design, production and technology. It is the biggest event entirely dedicated to professionals in Canada and on the East Coast. Over the years, this event has grown into something quite important by promoting all aspects of the gaming industry in an open, intimate environment.

“We thought it was important to offer continues training to everyone,” said Marie Claude Bernard, Director of Communications and Public Relations. “It’s really a great way of mixing everyone so that programmers could network with artists who could then network with businessmen, so on and so forth.” With Montreal being a major game development hub, it’s no wonder that MIGS has grown to such a degree.

Having taken place November 8th and 9th at the Hilton Bonaventure Hotel, MIGS 2010 consisted of almost 70 speakers focusing on various topics in the industry including the importance of mathematical style game theory, level design prototyping, and the design process and technology behind augmented reality games. Each speaker managed to provide, in intricate detail, the importance of that topic, the process of it and the aspirations tied to it. Not surprisingly, unification became a constant theme in this year’s event.

In David vs. GoliathVille: Sage Advice for Indie Social Game Designers, Scott Jon Siegel, game designer at Playdom, defined the notion of success in the world of social video game development as well as the negative stereotypes surrounding the social gaming market. Siegel also examined how independent developers can gain a clear competitive edge by not being afraid to innovate.

“There’s been a growing resentment towards social gaming,” explained Siegel. “I think the space is seen as non-permanent, unimportant, and not really capable of anything significant… I think there are a lot of bad stereotypes. I think it’s a lot of people seeing the current games that are out on social networks and assuming that’s all the industry has to offer.?

In Siegel’s view, he sees social gaming as being a step in the right direction, but is, unfortunately, being ignored by developers due to broad generalizations. “Those current games are wonderful in a lot of ways and successful in a lot of ways, but they’re not successful in the way indies see success. And it’s not anywhere near the potential of the space, either from a creative perspective or from a product perspective. There is a definite value and importance of this space, one that I feel indie developers need to work with,” said Siegel.

Siegel’s qualm is an important one, one that could potentially bring about a drastic change in both the social and indie gaming markets. Siegel noted that by working together, social and indie games could merge their particular sentiments to form a hub full of communication, entertainment and creativity.

“We have to admit the indie community doesn’t get social games… because they dislike the approach of the largest companies and biggest games in the industry… but they are universal; there’s no reason for them not to be working together in this day and age.”

Similarly, Julien Merceron, Technology Director for Square Enix, has worked to bridge the gap globally with the merger of Square Enix and Eidos in 2009. At this year’s MIGS, Merceron delivered a talk about the challenges facing his company in forming a global tech strategy which incorporates the needs of Japan and the West. Despite the deep cultural differences, Merceron expressed that the unification process (in both technological practices and cultural differences) has been much easier than many had expected.

“So far there haven’t been that many difficulties because there is this huge excitement,” said Merceron. “In Tokyo they really want some form of collaboration to happen. They’ve been looking for this kind of collaboration.”

And according to Merceron, the West seems to reciprocate. “Eidos is intrigued by the idea of working with a Japanese publisher and developer. I would say that on both sides they were so elated to share knowledge and look into potential collaborations that, so far, we haven’t hit any problems.”

Even so, underlying cultural differences still manage to arise. One major hurdle in Japan is that “in the West, it’s seen as being very cool to be making games. In Japan, not so much – especially for programmers,” Merceron said. “Programmers will tend to look for other types of jobs in the technology space. Gaming is probably not the first option for them. Unlike in the West where you can find a lot of superstars in programming, it will be a lot less in Japan.”

Although there are clear differences between the cultures, Merceron expressed optimism regarding language barriers (in terms of technology and tools). “We absolutely need to speak the same language. Even though the nature of the games can be different, it might be necessary to use different technologies on different games. And so this is something that we’re doing right now is making sure that we all have the common understanding of what technology is how it should be designed, what the fundamentals are, what platforms we need to support, how they’re gong to address graphics and lighting etc,” said Merceron. “We just need to have common definitions and a common goal.”

During Day 2’s opening Keynote speech, Ron Carmel, co-founder of indie studio 2DBoy, examined the crucial steps involved in developing an independent video game and, more specifically, to urge large publishers to use their resources to create small internal teams that would work on groundbreaking games from within. Once gain, unification is key.

“We need a medium-sized design studio. Something that is larger than a typical indie, but has the same tendency of talent density, focus and risk-taking,” said Carmel, formerly an employee of major publisher Electronic Arts prior to going independent.

“Creating this within a major developer doesn’t present a problem,” added Carmel. “With a budget of $1-$2 million dollars, 10 staffers could be hired to work on “creatively ambitious and forward thinking projects.”

While this notion seems unlikely due to budget and time restraints, it is, in fact, close to reality. Mainstream and indie developers have already taken drastic risks in the game development process and have worked their way that much closer to this ambitious and inspirational goal. What is important is the intent that the game developer has.

He also said that developers must move away from the notion that a team comprised primarily of programmers and artists can create a great work. Why do Valve’s games have such amazing environments? Because, said Carmel, “Valve has architects on staff.”

“Because games are, in a way, a superset of all the mediums that came before them… we need to incorporate the people who are at the top of their respective fields into our game design process,” said Carmel.

However, he said, that doesn’t mean just hiring them onto projects in limited roles. In his view, everybody has to have their hands in the project. “Cross-pollination [creates a] more cohesive [game] experience because everybody holds in their head the full vision of what the game is supposed to be.”

That said, unification forms a large role in how a project is constructed. If developers, big or small, could combine their skills with other professionals to form companies that can work on a higher budget while still being both creative and forward thinking, than those projects will more likely reach their max potential.

In Carmel’s view, generalizations are best avoided. He doesn’t see a lot of differences between indie developers and mainstream developers. Rather than “indie” versus “mainstream”, Carmel would view the split as “design studios” versus “commercial studios” – the goal of design studios would be to try new ideas and aim towards creativity, and the goal of commercial studios would be big productions generating a lot of money. When we concentrate, as an industry, on “practices rather than identity, then we can talk about the meaningful differences in our games without creating conflict,” said Carmel.

In the gaming industry there are various roles. Some people want to inform and promote the industry and niche corners of that industry while others try to express the process behind their work, but in actuality they all have one similar, and important goal: to create a stronger, universalized gaming industry. That may seem like an arduous task, but it can very well be done and has been done on countless occasions already.

Within two jam-packed days, MIGS had cemented itself as being one of the most important gaming events simply because it allowed for both a sense of intimacy and understanding – intimacy because of its personal recollections from industry professionals and understanding because of its vastness in informational range and clear, focused mandate. While few developers believe that the true potential of gaming has been achieved, events such as MIGS let us stop and think about that notion and discover the depth behind this fast-paced industry.