I’m a pretty good guy in real life. I offer my seat on the bus to old ladies, I always tip my waiter and I even let telemarketers finish a few sentences before hanging up on them. Sure, I’m not perfect, but I like to think if some higher power handed out morality report cards I’d at least get a passing grade.

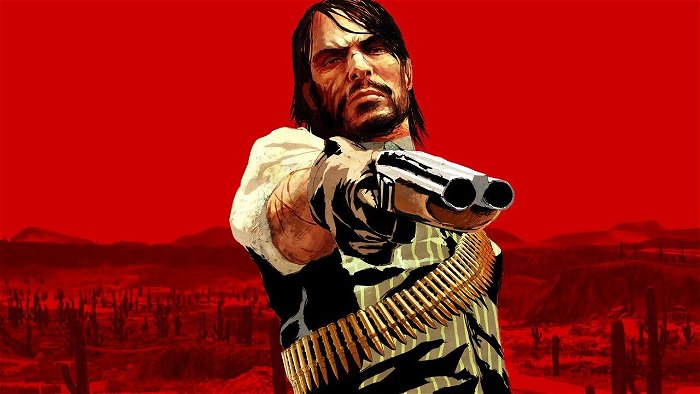

The story is a little different in games though, particularly RPGs. Given the choice to play the saint or the sinner, I invariably chose the darker path. Whether it’s chowing down on crunchy baby chicks in Fable II or tying innocent women to train tracks in Red Dead Redemption, I relish being a jerk.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fG1LgOlNxI

As games have evolved over the years, they’ve gotten a lot better at letting the player craft a narrative based on their own decisions. Players have more say in shaping the story of a game than ever before. Despite all of this advancement, the path of the hero and the path of the villain are often almost identical.

Outside of a few side missions scattered throughout the main storyline, choosing the immoral path rarely has any real effect on the world at all. Sure, the final cinematic might be altered, but the road to the end really isn’t very different. A majority games with moral elements only matter at few pivotal points and only a few elements are ever altered at those points.

This lack of distinction is where I take issue: if a game provides the player with the option to choose evil, they should let the player experience the consequences of those actions properly. The reason evil is attractive, the reason why I want to be a bad guy, is that they defy the systems of order the rest of us adhere to, regardless of penalty. Those who lie and cheat and steal break the rules of society – even to self-destructive ends – just for the thrill of it.

In games, this disregard for consequence is trivialized by a constant need to keep rewarding the player regardless of action. You may not get that +2 Sword of Holy Power after killing all the helpless villagers, but somewhere down the line you’ll pick up a +2 Axe of Blood instead. Everything has its checks and balances, and the player gets a pat on the back no matter what they do. This is no good if we want morality to matter; sometimes there needs to be real loss in order for players to feel like they’ve made a choice, good or bad.

Dragon Age: Origins is probably the game that most aptly executes this principle. Instead of a slider bar dictating karma points, every choice has an effect on relationships with other characters and can ultimately lead to them abandoning the party forever with no gain to the player whatsoever. When these characters leave, you feel their scorn and, if you’re doing it on purpose, you feel like the asshole or martyr you set out to be.

If games are meant to make us think critically about our decisions, then they need to make us reflect through consequences, even if this means making the player suffer for their choices. Game developers need to stop rewarding players for every possible outcome and start using the power of loss to accentuate the rebellion of evil and the sacrifice of good.

Being good or evil isn’t just about the individual choices we make; it’s about facing what those choices mean in a grander context, even if that means no benefit other than understanding more about who we choose to be.

This article first appear in the October 2010 issue of CGM.