This is part two of a two-part history on the Canadian videogame industry. Here CGM focuses on the indie side of things, and how independent developers have become the face of the Canadian videogame scene. Be sure to also check out part one, detailing the inception and rise of the industry in Canada, from a AAA perspective.

Flash back to 2004: Ubisoft Montreal is fresh off the release of Prince of Persia: the Sands of Time, and EA Black Box is reveling in the success and neon glow of their new Need for Speed: Underground series. It’s then that a two-person team in Toronto, calling themselves Metanet, release their game N as freeware on AddictingGames.com. N went on to win the Audience Choice Award at the 2005 Independent Games Festival (IGF), and become one of the festival’s first “success stories,” before spawning a sequel: N+ for Xbox Live Arcade (XBLA) in 2008. N+ had the lucky distinction of being one of the few pre-Braid XBLA megahits; if you had an Xbox 360 and an internet connection at the time, you probably owned (or at least heard of) N+.

Seeking help to port N to XBLA, Metanet reached out to developer Klei Entertainment in Vancouver. While Klei would eventually pass on development of N+, they would not fade into obscurity; in 2010, Klei released their second original game, Shank, which stayed in the top XBLA games for more than a month. In 2012, Klei’s Mark of the Ninja attempted to redefine stealth gameplay by allowing players the agency to finish the game without killing a soul, and it found critical acclaim in doing so. Not unlike Jarome Iginla at the 2010 Olympics, Klei followed Shank and Mark of the Ninja with a third critically acclaimed game for a spectacular hat-trick; Don’t Starve, a survival roguelike, earned Klei a spot as a finalist for the IGF Grand Prize (the gold medal of the indie Olympics) earlier this year.

Klei was hitting the proverbial ice with a stride, but the Vancouver indie scene had already begun taking shape: In May 2010, a meet up group (inventively called the ‘Vancouver Indie Game Developers’) was revealed as a monthly, social meet up for developers in the area to showcase and share game demos and ideas. After becoming unprecedentedly popular, the group rebranded as “Full Indie” in March 2011 and offered a larger, 100-person venue, as well as an annual Full Indie Summit, for what was quickly becoming a stable community of developers. Following the rising popularity of the first two Global Game Jams in Vancouver, in 2011 Full Indie started their own annual Full Indie game jam—the eventual origin to Vancouver’s next big game: Towerfall.

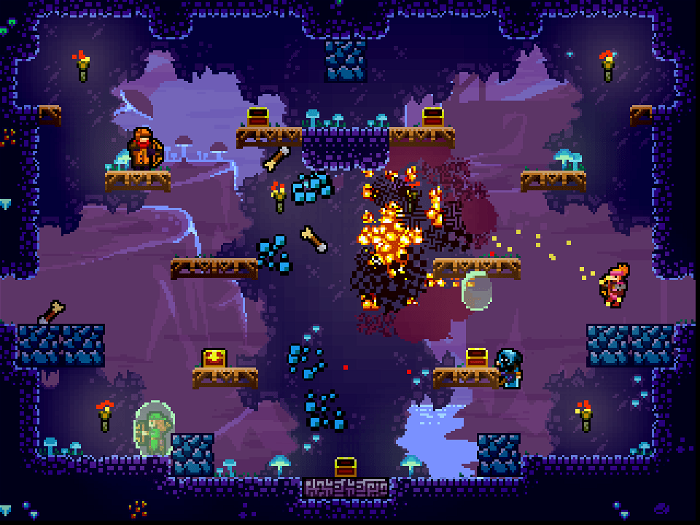

The development of Towerfall became a spectacle for the entire Vancouver games community. Conceived by Matt Thorson during the 2012 Full Indie Jam, Towerfall and Thorson’s Indie House, a group-home of sorts for community friends and fellow starving artists (aka game developers), became the face of the Vancouver indie scene right in tandem with Full Indie, where Thorson would bring playable demos of his game. Towerfall was born to be a cult hit; it offered competitive, local-multiplayer-only arena-battles on the desperately lacking Ouya console, and it even spawned a tournament scene. The game was a finalist for the 2014 IGF design award, and, in April, Eurogamer reported Towerfall had reached $500k in sales. In the end, Towerfall was not just Thorson’s success, but Vancouver’s.

The east wasn’t the least, however—in fact, Toronto was the city pioneering the indie scene in Canada, despite all the attention on Vancouver. TOJam, Toronto’s official game jam, began its annual run in 2006, and Gamercamp, Toronto’s summit of developer panels, ran for five years starting in 2009, predating Full Indie Summit by four years. Greater Toronto indies were pumping titles like blood: Freebird Games released the celebrated interactive-fiction adventure To the Moon in 2011; Drinkbox Games the culture-infused metroidvania Guacamelee! (2013); and Blue Isle Studios Slender: the Arrival in 2013; to name a few.

|

Game (year) |

Developer |

Sales (copies) |

Metacritic |

|

N+ (2008) |

Metanet Software |

450 000 |

83 |

|

To the Moon (2011) |

Freebird Games |

81 | |

|

Sword and Sworcery (2011) |

Capybara Games |

1.5 Million |

86 |

|

Fez (2012) |

Polytron |

1 Million |

90 |

|

Guacamelee (2013) |

Drinkbox Games |

88 | |

|

Don’t Starve (2012) |

Klei Entertainment |

1 Million |

79 |

|

Towerfall (2014) |

Matt Thorson |

33 000 |

87 |

|

Slender: the Arrival (2014) |

Blue Isle Studios |

100 000 |

65 |

Perhaps the most important release to come out of Toronto however, was Craig Adam’s and Capybara Games’collaboration, Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP (S&S:EP). An iOS original (and one-year exclusive to the platform) S&S:EP was released on the App Store at a premium price of $5—the kind of price only seen successful with big budget games, such as Infinity Blade, before it. Well-polished and innovative—by making intuitive use of iOS device features, such as the accelerometer—the game was unlike anything on the market which, at the time, was especially saturated by simple, freeware puzzle games. S&S:EP quickly became a turning point for the mobile platform; it paved the way for novel, experience-driven puzzle adventures such as Year Walk (2013) and Monument Valley (2014), and proved that console-quality titles such Limbo and The Walking Dead had a home on the small-screen as well.

S&S:EP wasn’t alone; pixel-art puzzle adventures were pouring in like the Great Wave of Kanada. Montreal-based Polytron’s pixel-art adventure Fez was in development for five years, supported financially by the help of a Montreal Telefilm grant, before its release in 2012. The wait seemed to be worth it; Fez became the Grand Prize winner at the 2012 IGF awards, following none-other than the 2011 winner Minecraft, and the saga of Fez has since become ubiquitous not only to the indie game scene, but the industry as a whole.

In just 10 years, Canadian indie developers created a community so simultaneously tightknit and inclusive that grandmothers started taking notes on how to make their Christmas sweaters. A 2014 Entertainment Software Association (ESA) report said that 53% of developers in Canada considered themselves independent, and more than half of those became so within the past two years. The shift in developer paradigm likely came in part from a honing focus from the Government of Canada; currently, Ontario and Quebec both offer some of the highest tax credits for game developers in all of North America, and the Canadian Media Fund Experimental Stream (CMF) offers game developers funding upwards of one million dollars. Kickstarter funding has helped as well; since launching last year, 67 Canadian videogame Kickstarters were selected as Staff Picks (29 of which were successfully funded) totalling three million dollars in pledges. Canadian indies are building doors faster than the AAA studios can close them.

The Canadian games industry is far from a wasteland—in fact, quite the opposite; in November, the ESA declared Canada the largest producer of videogames in the world per capita. The community is continually growing larger and more vibrant thanks almost entirely to the indie scene; Full Indie now hosts upwards of 250 developers every month, and Toronto started its own Full Indie equivalent, Torontaru, last year.

If I had to call Canada a hat, I wouldn’t call it a toque—if anything, we’re a sheepskin ushanka. But we’re not a hat, we’re that Christmas sweater knit with passion, historic talent, and some fur from those hibernating AAA grizzlies. We warm the industry with community and give a loving embrace to some of the biggest (and indiest) publishers and developers in the world.

As the ancient proverb goes: All your games are belong to us.